The Temple of Utmost Pleasure and the Journey Home

Part III: The End of My World-Building

I’ve now spent far longer than I ever intended, looking back on my adolescent and early adult world-building efforts, and am starting to feel a little like a sort of amateur Christopher Tolkien mining the far less rich literary vein of my own youthful scribbles. But, since some have found it at least somewhat interesting, and since it may well be good for me to engage in this joust with humilité, I will take up a third lance to take one last run at the subject.

As I mentioned at the end of my first foray, before getting side-tracked by my attempts to forcibly Christianize my world, the “final” mental state of my world-building was produced by the integration of a short story that I did not initially conceive as being part of the world of Alathaa. But, before I get to that story and its integration, we need to establish the state that my world was in.

The State of Alathaa and Its Relation to Earth

As we have seen, my first attempt to Christianize Alathaa took the form of “high fantasy”, attempting to establish God as Trinity as the Creator of the world, and an incarnate Son of God as the Saviour of that world in terms of my world’s militaristic focus, which had the interesting result of producing a story that roughly paralleled the ancient “Christus victor” narrative without me even knowing about the ancient tradition at the time. But I was dissatisfied with the result, feeling even then that this approach to inserting God into my world came across as pretty heavy-handed and amateurish, and thus took a new tack, establishing a Sci-Fi-based continuity between our world and Alathaa, in which the inhabitants of the new world originally entered it from our world through a wormhole-style “flux zone”—but then abandoned that new narrative thread pretty quickly as I came to recognize this new story was itself pretty heavy-handed and amateurish.

However, the new “portal”-based approach to establishing some continuity between my fantasy world and our own had a number of advantages that led me to develop it further, rather than abandon it outright, not the least being not having to re-invent Christianity in Alathaa, which I instinctively felt to be beyond my capabilities. Thinking about the impact that being in a new world would have on the Christians seemed a much more manageable project. Two other important benefits to having humans arrive as colonists from our own world were that (1) it would obviate any need to explain why the main inhabitants of this world were human beings, just like in our own, and (2) it would allow me to carry over from our own world whatever ideas and influences I wanted to explore.

A key component of this Sci-Fi trip to Alathaa was that it would be one-way. This would allow my world to develop independently of our own, and would give references back to our own world that greatness-of-the-ancients and other-worldly feel that haunted the Middle Ages and has become such a hallmark of modern fantasy. I do not know what, if any, influence Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern saga had on my thinking here—I certainly loved her Harper Hall trilogy, at this point, but I don’t think I got into her larger world until later—but it’s interesting to note the parallels between McCaffrey’s approach and mine here, as well as the differences: she established a Medieval-fantasy feel in Dragonflight in order to deliberately move away from it as Pern is modernized through a Renaissance/Enlightenment rediscovery of the Ancients’ technologies and ideals, while I wanted to re-establish and preserve that Medieval sensibility and ultimately make it impossible to escape.

To achieve this, and to bring the Sci-Fi component of the transition back within the scope of my abilities as an amateur “hard-Sci-Fi” writer, I brought the portal to Alathaa back to Earth (rendering accurate accounts of space-travel unnecessary) and made the colony established on the Alathaan side of the portal a top-secret scientific project (always a useful trope to explain why no one in our world knows about the connection). Then, not long after the Alathaan colony had been established and populated, the natural transformative energies (magic) of the Alathaan universe that roughly corresponded to our world’s electrical energies, reasserted themselves, causing the portal between the worlds to collapse, and the Earth-technology-dependent colony to become untenable.

Three important effects on the world of Alathaa (over and above the all-important permanent separation of Alathaa from our world) arose out of this Tower-of-Babel-style moment:

The colony was destroyed and its human inhabitants were scattered, becoming the progenitors of the various cultures and nations of Alathaa.

A last-minute attempt to save the entirety of human knowledge by printing out the whole of our great works of literature resulted in the Codex, a deliberately fragmentary record of the Alathaans’ Earth-past, which was further fragmented as the survivors of the disaster each took their favourite bits of the Codex with them as they dispersed.

The transformative nature of the Alathaan natural energies and the differing physical laws of the Alathaan universe

made the development of electricity and gunpowder impossible,

formed the basis of Alathaan magic, and

created, from the human survivors most affected by those energies, the hybrid races of “mythical” creatures which also populated Alathaa (fauns and centaurs and the like).

This, at least, is the end-state of my world-development as it has remained in my memory, since what few fragmentary expressions of this world as I put it into fiction have mostly been lost. As a world, Alathaa embodies many of my youthful ideals, being a world of magic and transformation which is permanently and necessarily Medieval, both in terms of its technology (with electricity and any sort of explosive technology being rendered impossible by the world’s physical laws which are also the basis of the world’s magic), and its haunting memories of a now-unattainable more advanced and organized past.

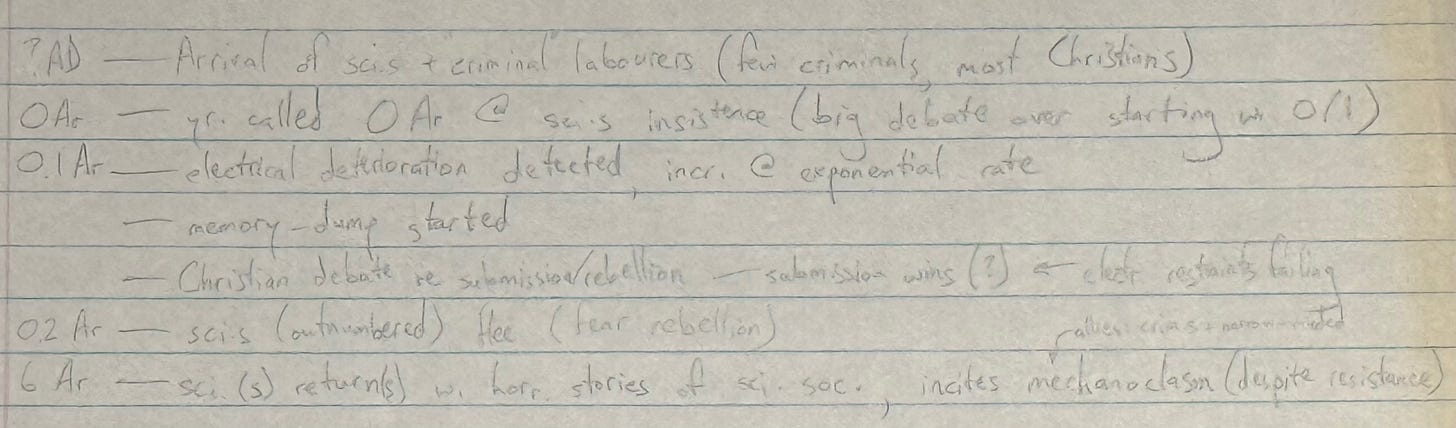

But this “end-state” was itself the result of multiple stages of development, a few of which are preserved in unfinished outlines and notes, such as this one which I believe belongs somewhere following my jettisoning of the space-based “flux zone” in favour of an earth-bound portal and colony, but which still preserves the Christians as a persecuted and imprisoned group, now not “hostages” but as some form of “criminal” forced labourers.

Much as I loved (and still love) science, scientific materialism (as embodied in the ruling class of scientists) was clearly the villain, hostile to Christianity, unable to understand it (as evidenced here by their fear of rebellion, even as the Christians have decided against rebellion), and ultimately their own worst enemies (as evidenced by the horror stories of “scientific society” that they relate upon their return). Also in evidence here is the beginnings of the “electrical deterioration” concept, leading to the initiation of the “memory-dump” which would eventually become the Codex. Perhaps my favourite feature of this fragment is the “big debate over starting with 0 or 1”, with the scientists (presumably influenced by the computer scientists!) insisting on starting the new dating system at 0 Ar (which I believe stood for “Arrival”).

The Temple of Utmost Pleasure

Into this slowly cohering world came a short story that I believe I wrote for my university creative writing class: “The Temple of Utmost Pleasure”. The story was not initially conceived as a part of Alathaa, as is evidenced by the non-Linyarathan names—although even as I eventually came to conceive of it entering into the canonical history of Alathaa, it came from a society separated from the others which would thus not have been influenced by the language. The story was a powerful one for me on many levels, not only because it was an attempt to implement some of the characterization that was so notably absent in many of my early attempts at writing, but, much more importantly, because it was an attempt to address questions of epistemology and religious knowledge in and through literature.

Despite being about the exposure of a clearly false religion, “The Temple of Utmost Pleasure” takes its inspiration from conversations about the Truth—what was true Christianity and the true nature of Reality—that dominated my discussions with my friends and family at the time. It is fascinating to me, in retrospect (this was written before my experience of the earthquake in Japan or my conversion to Orthodox Christianity), that the only positive end-point in the story is a rejection of received tradition in favour of a forgiving, collaborative experience of reality based on one’s own experience and the experience of those we’ve come to know and trust.

The story follows four youths, En (pronounced “Een”), Ju, Gid, and Abs, whose more experienced counterparts in the Temple are Fathers Och, Das, Eon, and Alom. The intent behind the splitting of the Biblical names here was both to foreshadow and to comment on, for those familiar with them, the nature of the conclusions each character would come to, and also just to come up with some nice foreign-sounding (but possibly still religiously evocative) names. The religion and the society that it shapes are a classic dystopia, founded upon a falsehood that has been communally accepted as the Truth: an asceticism in which everyone is encouraged to forgo earthly pleasure (other than a Temple-specific ritual called “Acupleasure”) in order to store it up for a final ritual called Consummation in which one is ushered into the afterlife by the spilling of one’s blood in a way that is supposed to be utterly pleasurable and thus echo into one’s after-existence. As Abs relates Father Eon’s teaching:

pleasure comes from the blood, so we dare not waste it in our day-to-day enjoyments or pleasure-seeking activities. After all, we each have only so much of it. Instead, we save our blood, using it only indirectly—like in Acupleasure—until that final day when Consummation is all there is left to experience. That’s when we release the blood-pleasure, and then all at once so that the blood adds immeasurably to the pleasure-echo of our beings in the afterlife.

While some of the details of the Temple rituals and theology are deliberately horrifying, and the resultant dystopic society is somewhat implausible, I still rather like the way the young acolytes’ debate over these details gets to the heart of how we know things, especially for those growing up within an authoritative religious tradition. And there are safeguards built into the system, as there are in every such society, in which those who question the Fathers are “given free Lesser Hall Consummations to prevent further turmoil of mind from completely messing up their after-existence.”

A key moment comes when the hero of the story, En, who has been questioning whether Consummation is, in fact, pleasurable, suddenly realizes that his questions—if all the teachings he has grown up with are correct—may have the potential to mess up his friends’ after-existence. He asks them the all-important question, “Do you trust me?” Then, as they agree, En hands over the silver nail he’s been fingering to his friend Ju, and gets him to use it to perform the Consummation ritual on him, whereupon all his friends watch En’s experience of the ritual and hear what he says as he dies.

The rest of the story recounts four responses to the event from four of the characters. Father Och, who walks in on the event, is deeply disturbed by what he witnesses and follows En’s experiential journey into death. Abs approaches Father Das, claiming En’s Consummation was his idea, undertaken for En’s own good—an explanation which Father Das accepts. They part ways, Abs muttering under his breath “something about a priesthood and revenge”, while Father Das smiles to himself, thinking that

With such promising young blood, and the sudden self-removal of En and, more importantly, of Och, the Temple priesthood could at last really get down to its business, the business of enjoying its followers’ Consummations.

The most important response, though, is Gid’s, with which the story ends and which I will present here in full:

Gid stepped up the stairs, every muscle tense, his mind completely occupied with the trivial task, as though all that was holding his body together was the wavering force of his will. And Gid still wasn't altogether sure that he wanted to keep holding himself together. But En— Gid tried to force the thought from his mind, but it was no use. But En had gasped out, as distinctly as his raw vocal chords had been able to manage, “Not this way. Pain. Not pleasure.” So Gid kept climbing, though the tears streamed down his face.

Once loosed, the harsh memories flowed as freely as his tears. The blood. The screams. Father Och's helpless protests. En's hoarse, ragged whispers. “Context. Seek truth…” A long and horrifying pause. “…elsewhere.”

Gid raised his salt-encrusted face. Before him, just a little further up the broad stone staircase, two huge oak doors barred the way. Every muscle in his body was screaming out, like En, but somehow Gid made it up the last few worn steps. He walked across the dais to a smaller door set in the thick wood of the huge right door, and collapsed against it. There was no truth here, or at least none men could live with. He straightened, opened the small door, and stepped out of the Temple of Utmost Pleasure into the rising sun. He unclenched a fist and a blood-stained silver nail fell, ringing, onto the Temple step.

Gid stepped forward onto the gravel road, weeping softly. En had been right. He would seek elsewhere for truth.

Revisiting this story thirty-three years later, I’m struck by its flaws, but I am still powerfully moved by this ending. And, with this being possibly the best piece I’d written up to this point, and with the desire to return to the world of Alathaa still strong within me, Gid struck me as the perfect uninformed noble-hearted character to set off on a hero’s journey to discover the true state of the world around him. The dystopic society of the Temple of Utmost Pleasure would naturally have isolated itself from the rest of the world around it—there being no way such a dystopia could survive without such isolation—and Gid, as a relentless and honourably motivated seeker of Truth, would then set off across the desert that separated his society from the other realms, nations, and cultures that made up the world of Alathaa, arriving just in time to witness the tragic destruction of the Ten Kingdoms and ultimately make his way to the relative safety of the Kingdom of Arath. This would bring my world-building full-circle, back to the place where I’d started, and I began the process of re-imagining my world accordingly.

The Last Pieces of the Unfinished Puzzle

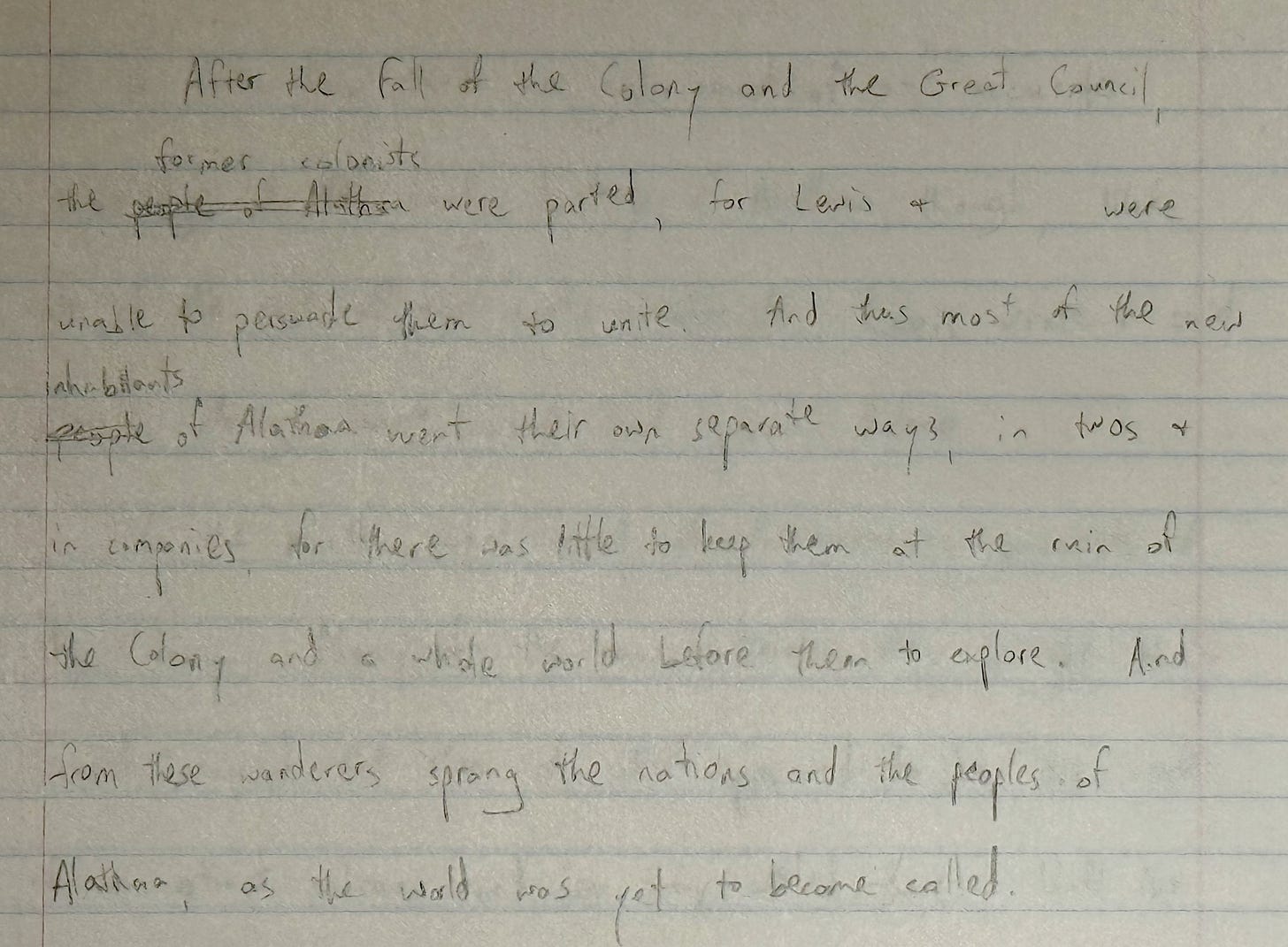

With the need for and initial impetus for a “hero’s journey” established, in which the uninformed outsider Gid would encounter the wider world, there was now an obvious need for the origins and development of that wider world of Alathaa to be more firmly and systematically established in order that Gid might encounter a fully fleshed out world in media res. Accordingly, I set out on what was fated to be my last stab at world-building, developing in broad-brush strokes an initial history of the world through the eyes of a pair of explorers, “Lewis + _______”.

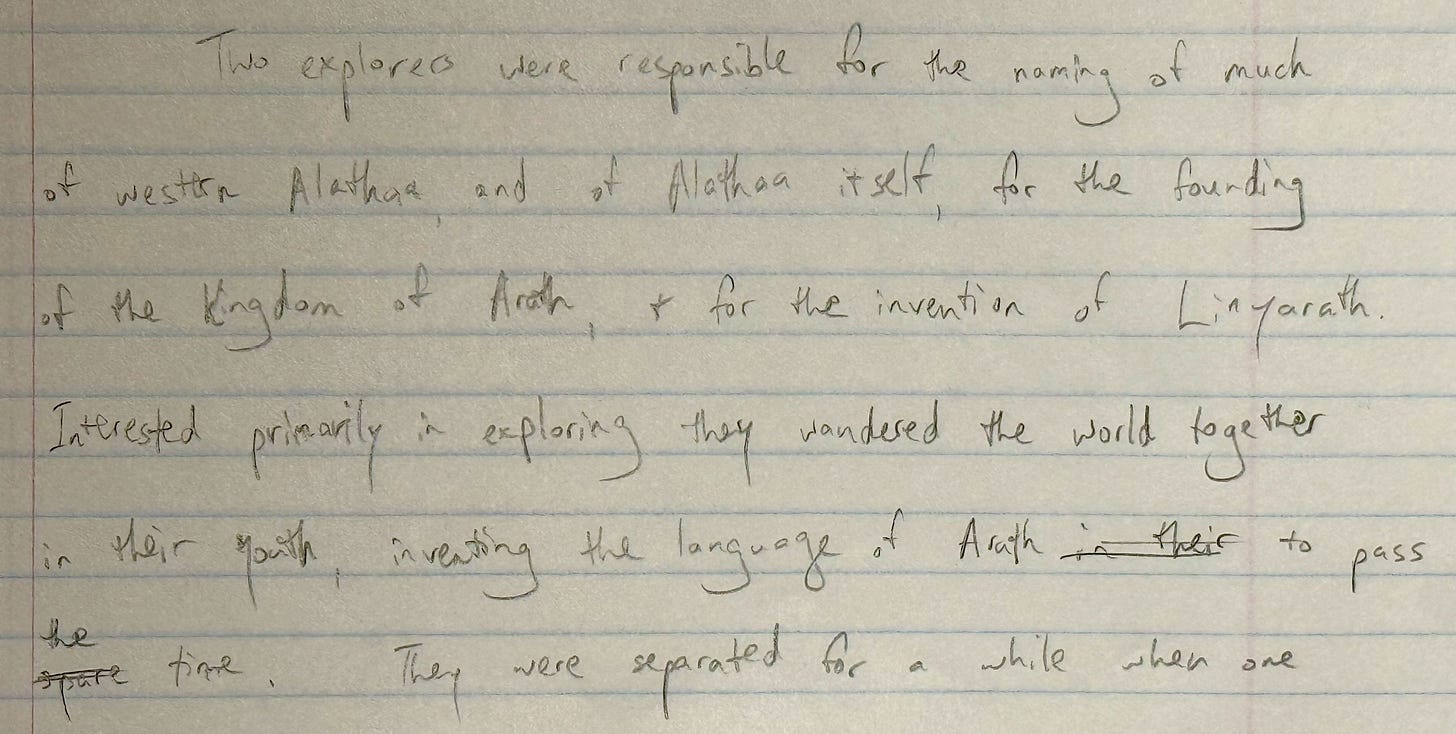

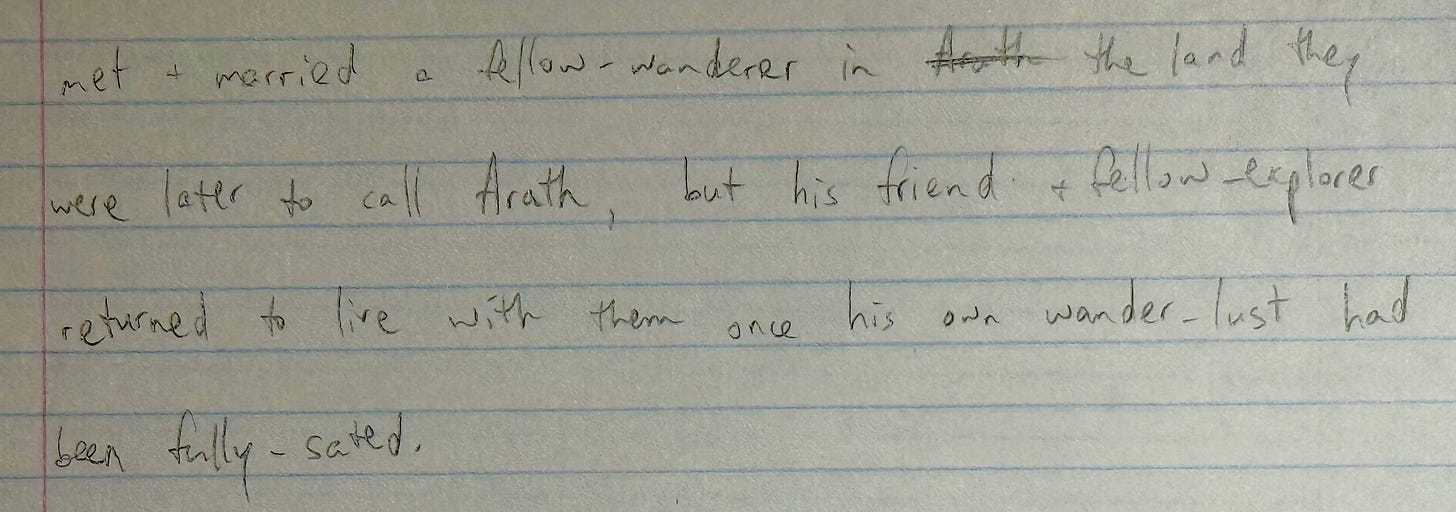

The logical next step, after the fall of the colony, would, of course, be for the colonists to meet together and discuss what to do next, which meeting would naturally, in time, accrue a name worthy of the significance of the event: hence, “the Great Council”. It is noteworthy here that the spokesperson for unity is named “Lewis”. I have some vague recollection that the pair of explorers were at least somewhat inspired by the famous “Lewis and Clark” (having visited the Lewis and Clark Caverns in my youth), but I then go on (in a crossed-out section) to describe Lewis as a “great speaker and philosopher”, and further describe the activities of Lewis and his unnamed companion as follows:

As you can see, I might as well simply have called them “Lewis + Tolkien”, but I suppose that would have been just a little too obvious. To be fair, it’s not an exact parallel, and I note in another passage that

Lewis joined himself to ten families who went west to live as a Christian nation, which was later to become the Ten Kingdoms. Lewis himself never took a wife, nor lent his name to any tribe, but became instead the first great historian and philosopher of the world of Alathaa.

But it is fascinating, as I look back, to realize that—whether I myself fully realized it or not at the time—I essentially made Tolkien and his wife and Lewis the founders and progenitors of the first and most important kingdom of my world, and made Lewis and Tolkien the ones who named the West of my world and invented its most important language.

Having established the Christian character of the Ten Kingdoms, I also began to flesh out the origins of some of the other important groups that had made appearances over the years, such as the northern wizards (descendants of the scientists) and the southern barbarians, as well as two new groups, the Librarians, a small group who stayed at the ruins of the colony to preserve the books rescued from the fall of the colony and to search for ways to reopen the portal back to Earth, and

To the east went a small and a strange group, seeking only pleasure for themselves, and these people were lost from history for a long time until the Great Awakening in that land.

With this incorporation into Alathaa of the society that would form around “The Temple of Utmost Pleasure” (including the “Great Awakening” there that was to be led by Abs), all the pieces were in place for the writing of my great epic—which never got written.

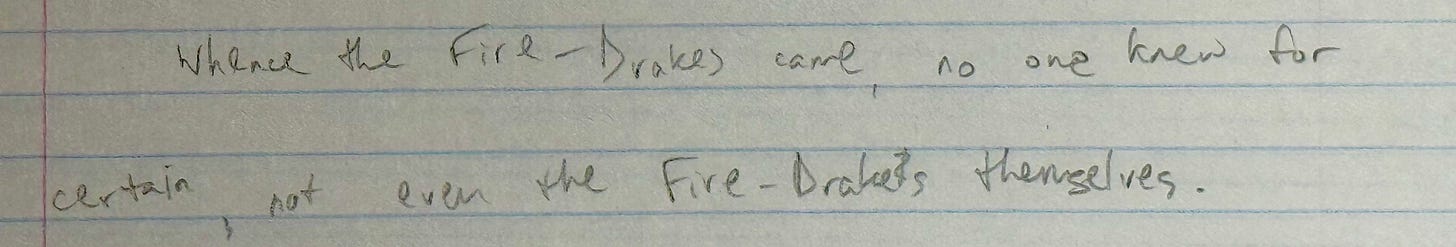

The manuscript which contains all this world-building ends abruptly with a final haunting sentence—one particularly haunting for me, as I no longer remember (if I ever knew) where I was intending to go with it:

There seems to me something oddly fitting about the fact that my unfinished world-building ends with the inexplicable arrival of dragons.

Making Sense of the World Through World-Building

I have never been a particularly organized or disciplined writer—or person, for that matter. 1992/93 was the year that I finally graduated from UBC with my Bachelor of Education degree: a traumatic experience (which I have documented previously) that led me to not want to teach in a classroom until my experience as a missionary English-teacher in Japan in 1994/95 made me realize that I actually enjoyed teaching students who wanted to learn. I made my living in these “wilderness years” working as a general tutor, teaching an ever-increasing number of ESL (English as a Second Language) students, which was what led me, ultimately, to work in Japan. It would have been a good time, in retrospect, to have written my epic fantasy—except for the fairly important fact that many of my most important life-lessons were not learned until Japan, and afterwards.

But the general outlines and concepts of the world I had built in my imagination stuck with me. Everywhere I looked I saw the importance of ideas, especially as embodied in literature, in the shaping of our society and of others. The real Codex, our Great Library of written works, is, in fact, a culture- and nation-building heritage and influence. And these ideas, contradictory as they are, are not passive or static: they are a primary source of conflict in our world, both intellectual and physical. Nor are our ideas neutral: they are, in fact, powerful forces, as they are enacted, both for good and for ill.

When I came back from Japan, it was with the intent to eventually return to Japan as a college- or university-level English teacher. Accordingly, I threw myself into the study of the great works of English literature, and completed all except the thesis of my Master of Arts in English Literature degree. But much as I enjoyed the study of those great works, as well as establishing one of the first websites on the internet dedicated to the sub-genre of Christian fantasy, the two courses that really stuck with me from this period both focussed on the conflict of ideas as embodied in literature and in the study of literature: the latter being the literary critical theory course which culminated in my “This Is Not a Frame—And Is” essay, and the former being a course on how various works of literature written during the reign of Henry VIII and the Elizabethan period helped to transform England from being the most Catholic country in Europe to one of the most solidly Protestant.

But I didn’t finish my M.A. thesis because, also at this time, I got drawn back into the then eight-year-old debate over whether or not the Orthodox Christian Church was, in fact, the “one holy, catholic, and apostolic church” of the Nicene Creed. And now the conflict between age-old ideas became personal, and the lessons learned through world-building and my stories became intimately and immediately relevant. If I was going to know the Truth, I couldn’t just rely on what had been handed down to me: it had to be consistent and it had to be rooted and grounded in both personal experience and the experiences of those I had come to know and to trust. And I had to know what the Truth was if I was going to fight for it, and, once I knew it, I had to be willing to give up everything for it—even to die for it, if necessary.

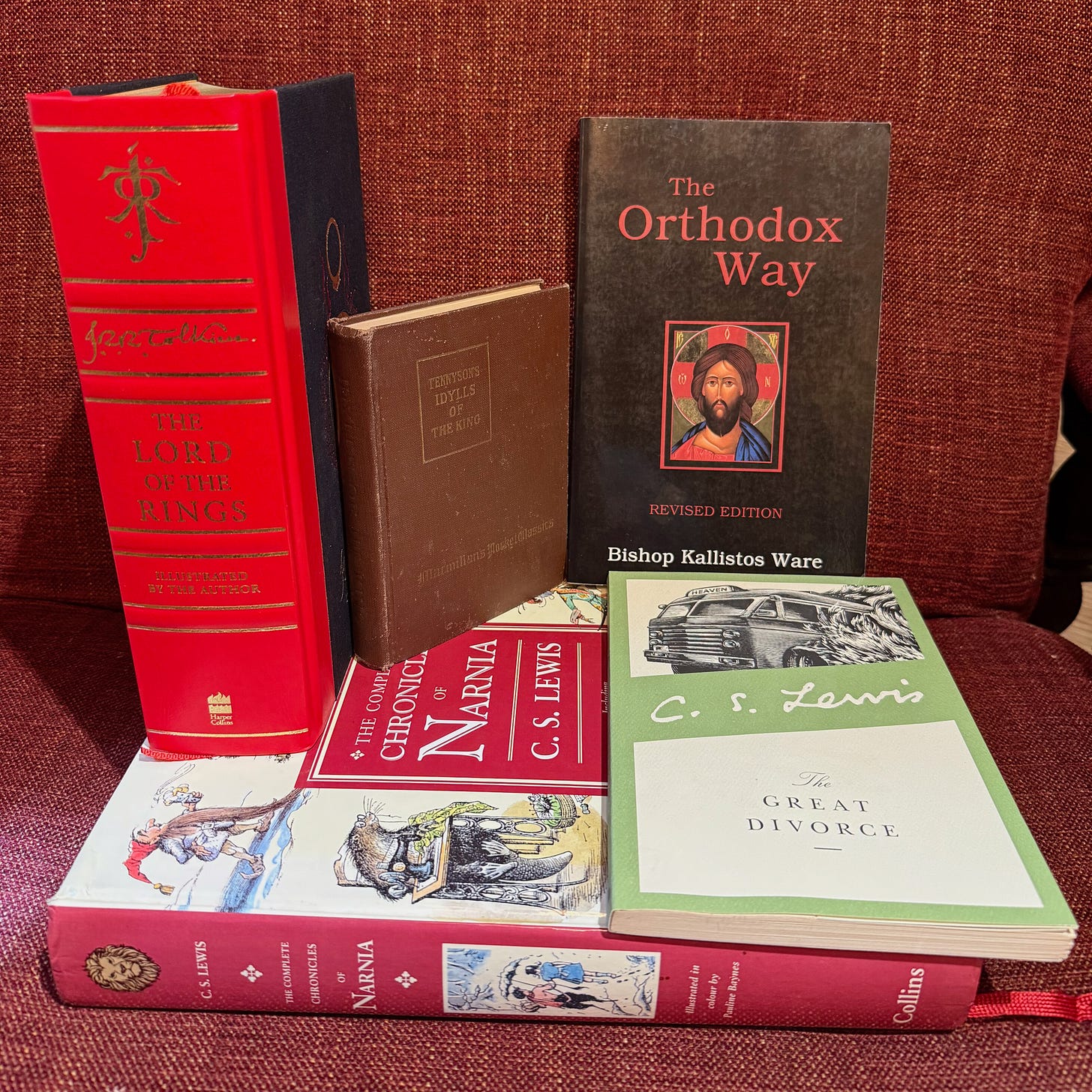

Without going into the details of the debate (which I have documented, in part, here, if anyone is interested in them), I found myself in the position of Gid, having to seek truth elsewhere than the tradition in which I’d grown up (though where I’d grown up had much more truth than Gid and En had ever experienced), and found myself flung into a wider, richer, more chaotic and more beautiful world than I had ever even imagined could have existed. The world that I ultimately ended up in was not the beautiful but fragmented and deeply divided world of the Ten Kingdoms, but, rather, a place where Lewis and Tolkien would both feel at home, deeply defined by books but even more deeply defined by collective experience: in the land between the mountains and the sea, I found my home in the Orthodox Church.

And, back at home, in the relative security of Arath, a funny thing happened. The books were still important—defining, even—but they were no longer as important as life. In the Orthodox Church, I got married and had children and I’d like to say I lived happily ever after until the end of my days, but I haven’t reached that yet. But it’s been pretty good so far—not without struggles, of course, but with a depth and a Medieval-style wholeness to life that I’d, up to that point, found only in fantasy.

Pretty much the last time I revisited the world of Alathaa—until just now, inspired by my daughter’s con-lang—was early on in my Orthodox Christian life, when I related the whole outline of my world-building, and the epic tale of Gid’s journey that would eventually have him end up in Arath, to my godparents. They encouraged me to write the story, but, strangely, I felt no real desire to do so. I think now that I had simply become too busy living the story: writing it down would have been but a pale shadow, a fantasy out-shone by a reality too rich for words.