Making Sense of the World Through World-Building

Part I: Childhood to Adolescence

Reading Tolkien often inspires world-building.

I began reading Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings when I was in Grade 7, but got stuck in Rivendell because I found the pacing was rather slow. But this roughly corresponds, I think, to the time when I really started to try to make sense of the world around me. Not in the basic experiential sense that we all do as children, but in the rudimentary beginnings of an adult sense, when I began to realize that there were countries and conflicts and history not just in literature, but in the same reality that I myself was engaged in.

I may be overstating the significance of this stage of my development, but most of my clearest childhood memories begin in Grade 6/7, and the two poems that I still consider part of my personal “canon”—“The Black Knight” and “The Vikings”—both date back to this period.

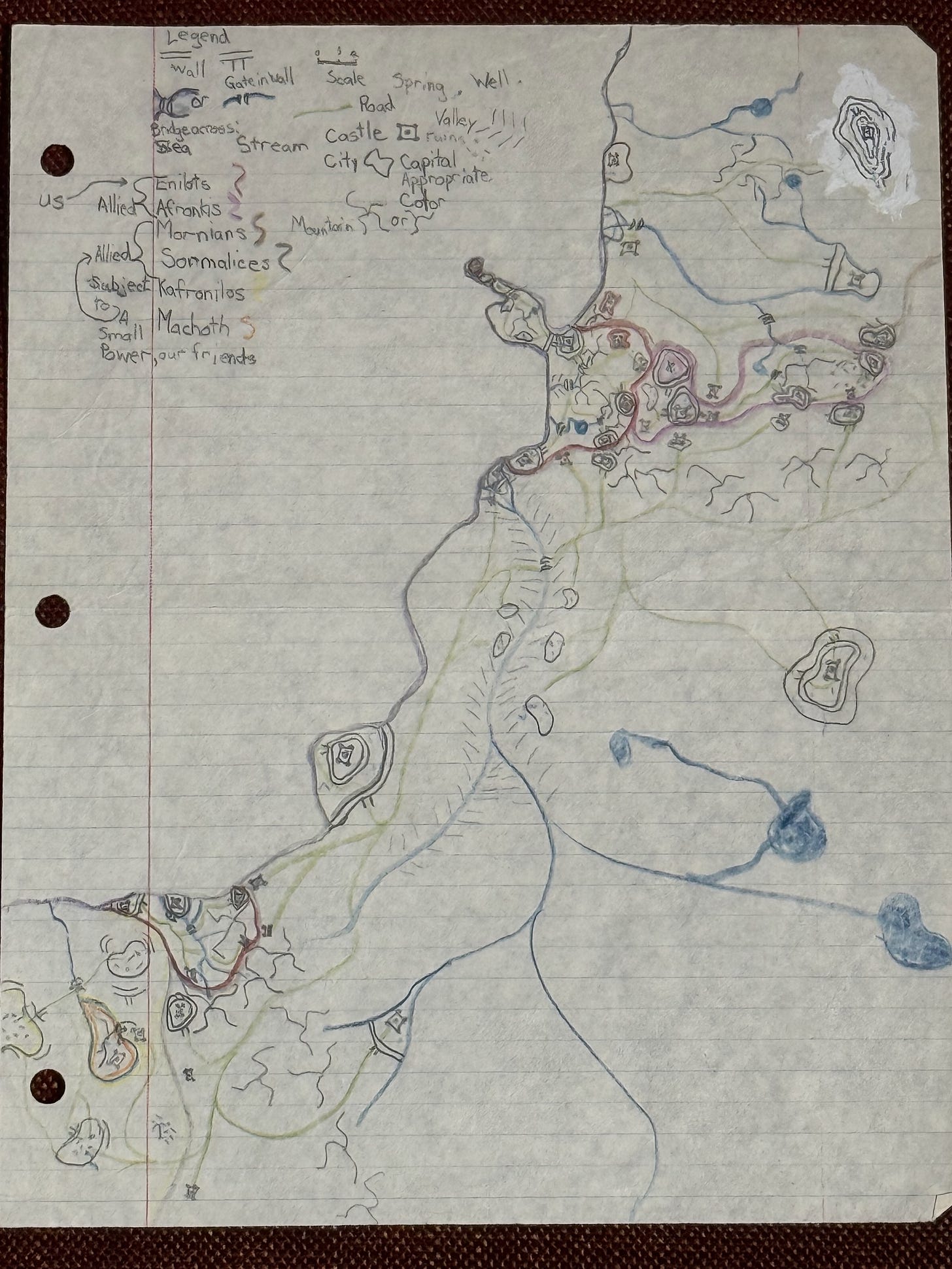

I was also more than a little obsessed with war at this point in my life, particularly medieval siege warfare—I loved castles!—as well as with maps, so it is perhaps not surprising that my first foray into world-building took the form of a map with castles and The Hobbit-style mountains on it.

There was no particular rhyme or reason to my place-names, at this point, but the geography of the little country I created here really resonated with me, for some reason. While there was no conscious inspiration for the geography of this map, I cannot help but notice, looking at it now, how much the overall outline resembles that of the maps of Israel that would have been in the back of my Bible, with my little country (here named “Enilots”) bearing a notable resemblance in both its location and its peninsula-and-island defensibility to Tyre. Another possible source of inspiration for this defensible peninsula-island configuration might have been Risk: I was always partial to the Siam-Australia strategy. And I’ve even considered the possibility that there might be some parallel between the “Enilots” peninsula and the way that Lower Mainland British Columbia (my home) is largely surrounded by mountains.

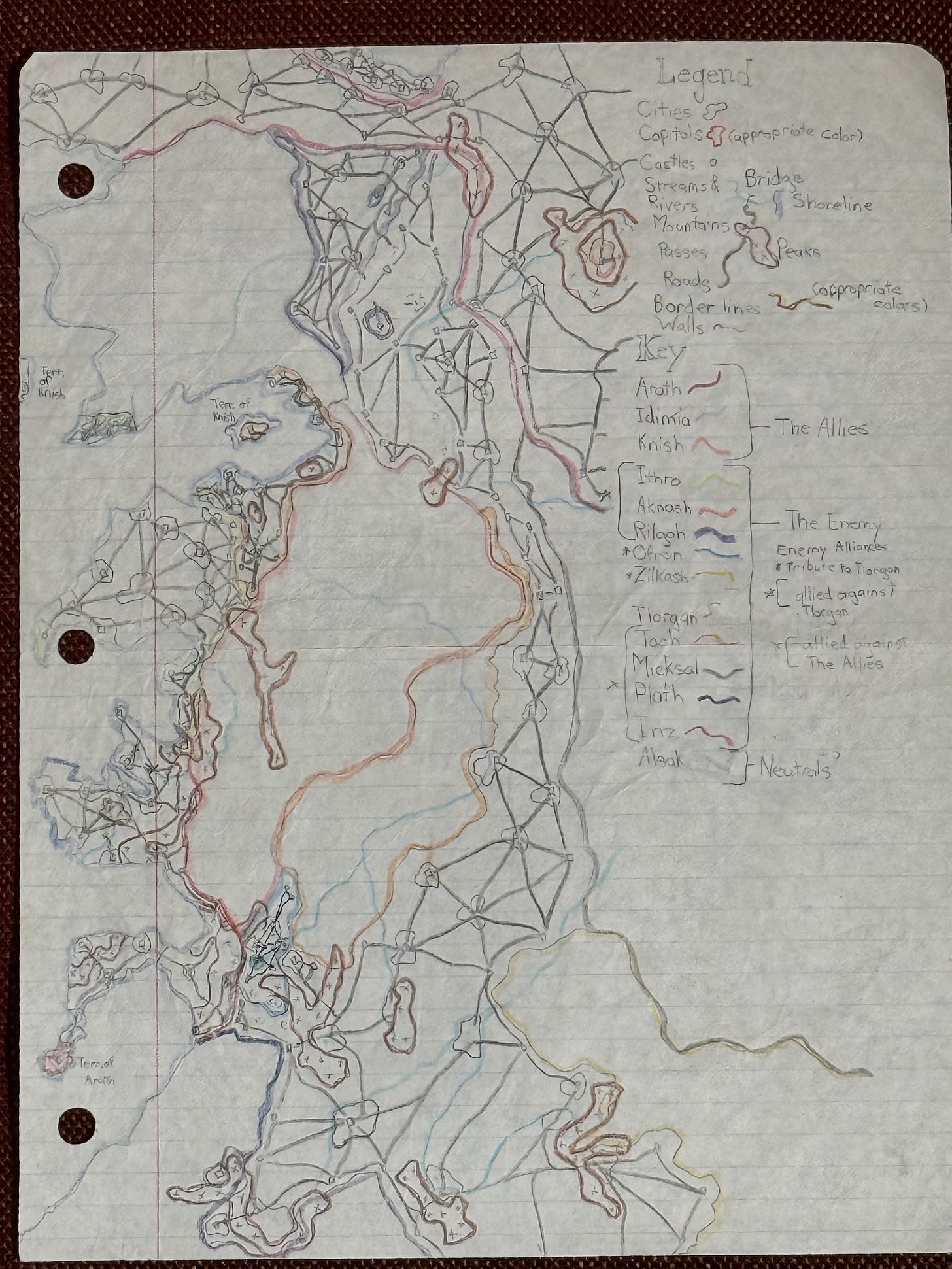

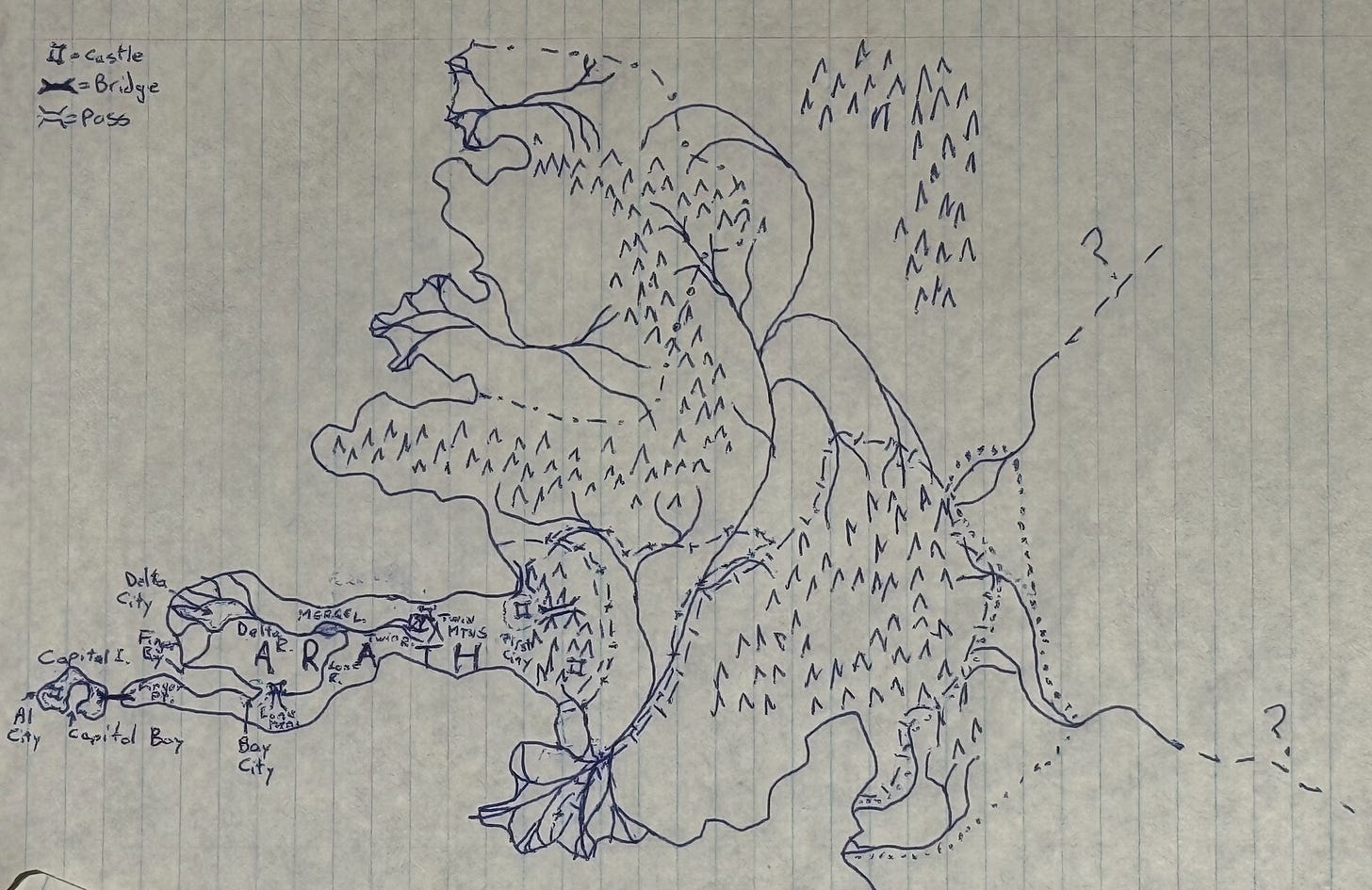

Be that as it may, the idea of the little peninsula-island kingdom surrounded by larger nations stuck with me, although the name did not. In the next iteration of my map, the same general geographic configuration is again “my” country, but this time it is named “Arath” and is now in the south-west corner of the map.

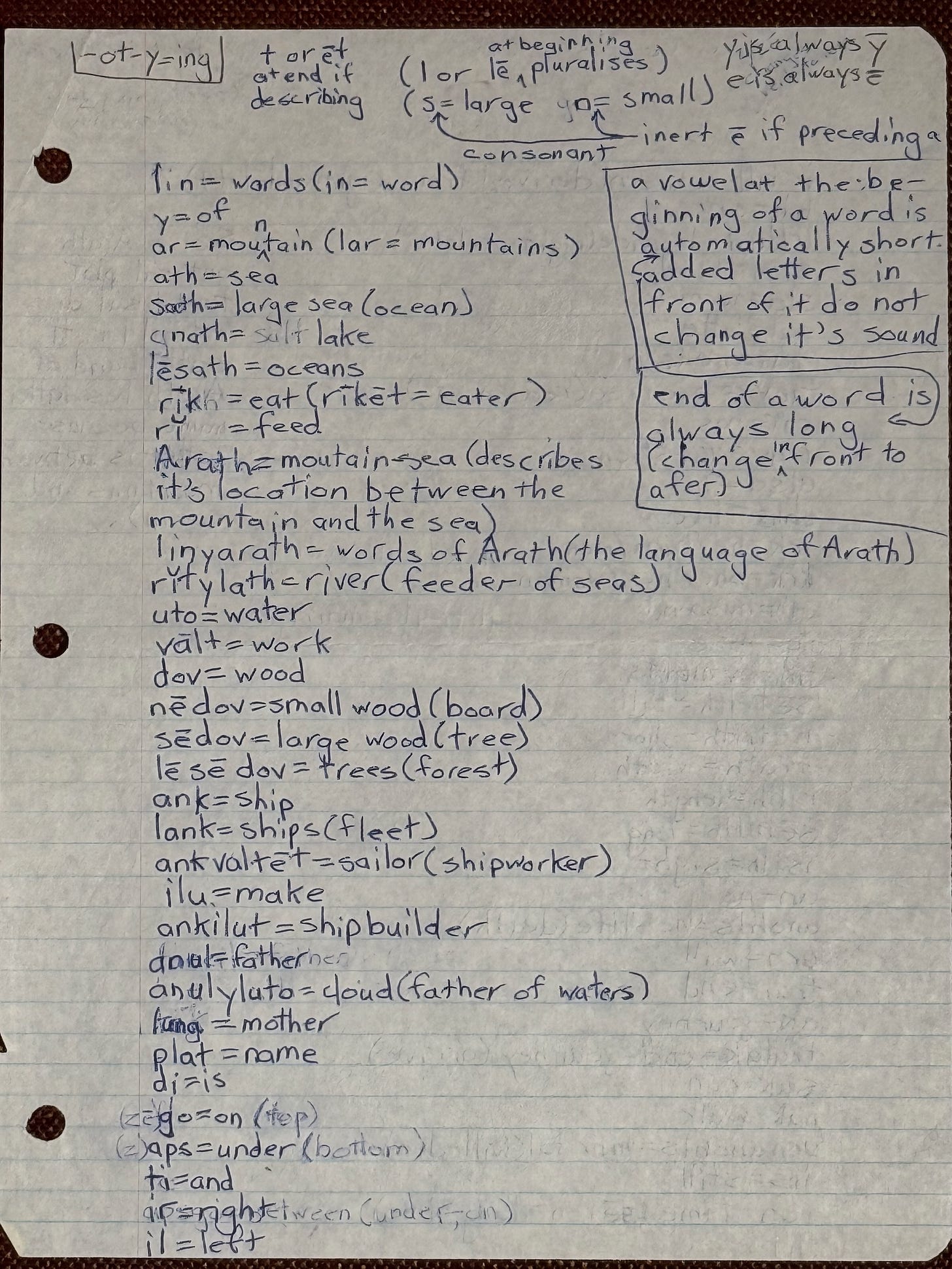

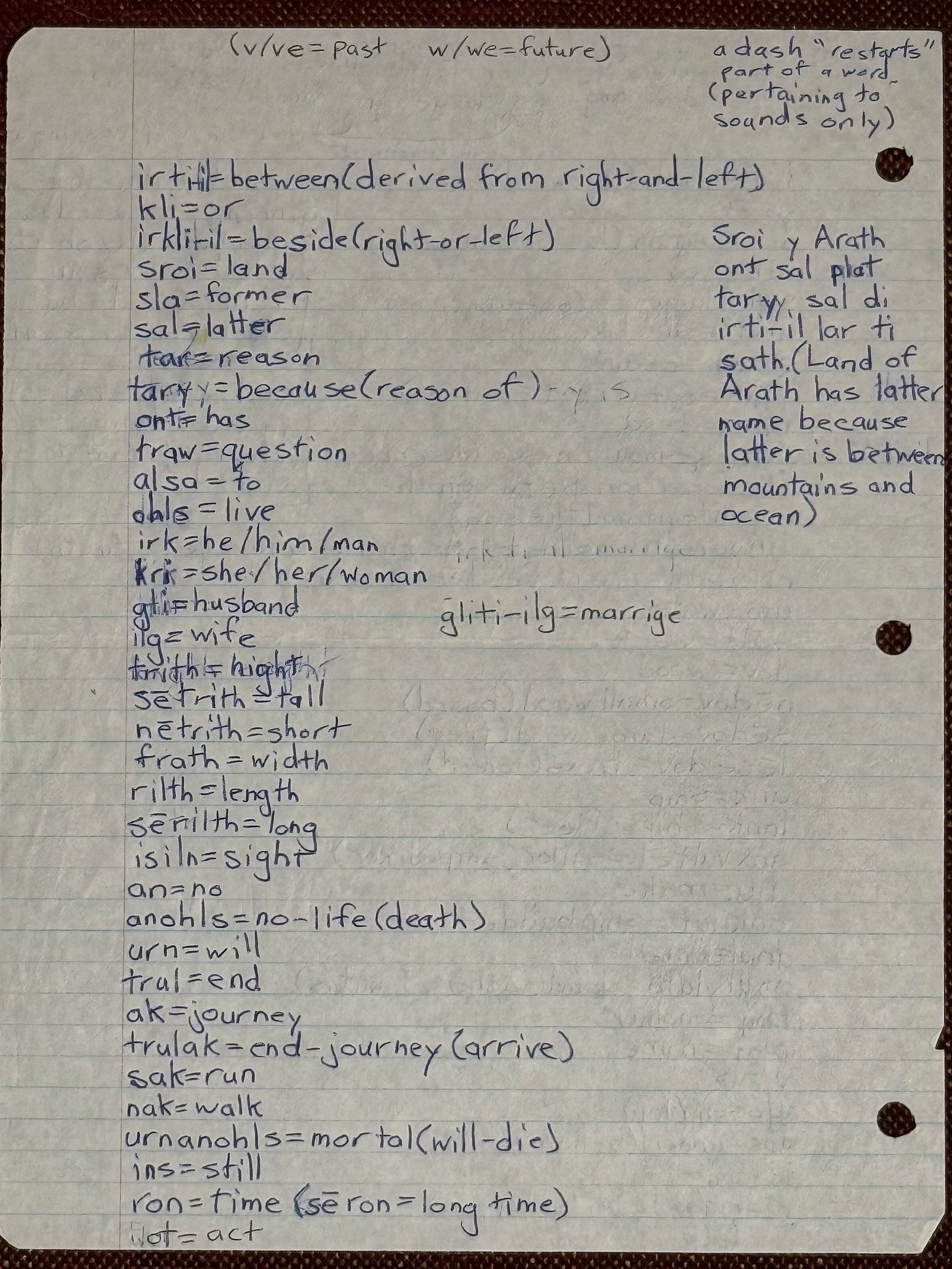

I’m pretty certain that, once again, there’s no particular rhyme or reason to the place-names, but that this time, as the place-name as well as the geography began to stick in my mind, and having finished most if not all of The Lord of the Rings by this point, the beginnings of the concept of a con-lang began to form in my mind from the place-name. Either way, given my previous map, it is plain that in my approach to world-building, geography is primary and language is secondary. But, with a growing love of language and of Tolkien, constructing my own language became more or less inevitable.

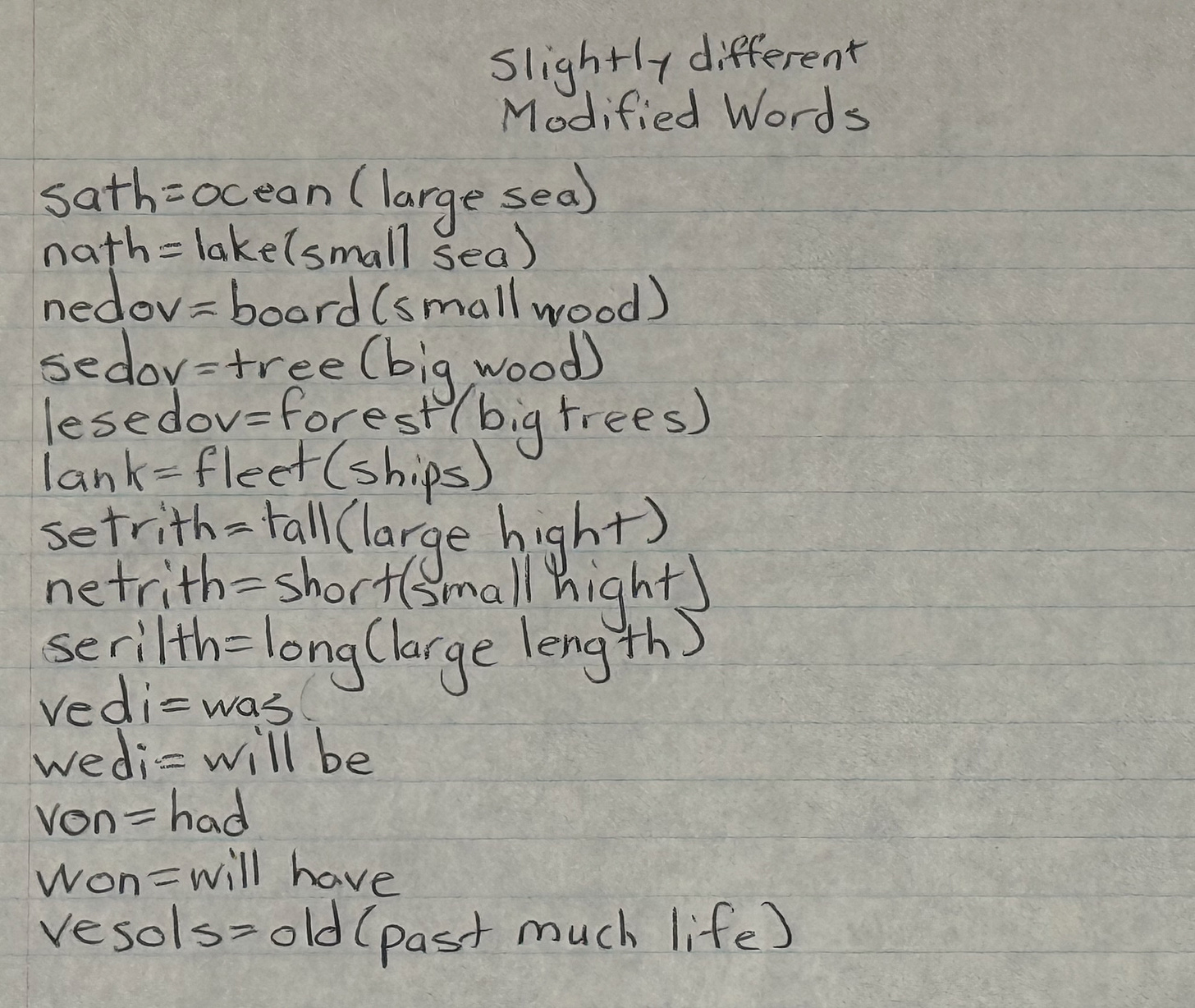

My approach to language construction was, I think, heavily influenced by my love of “root” words and etymological lore, and potentially also by the fascinating concept of a “basic English”. With the name “Arath” as a starting point, I broke the word down into single-syllable components, and, with the idea of the name deriving from a description of the country’s geography, “ar” became the word for “mountain” and “ath” became “sea”: that is, Arath is the country between the mountains and the sea. Then, of course, I needed a name for the language itself, and, continuing with the single syllabic roots, “lin” became “words” and I took consonant-“y” as designating“of”, making the name of the language of Arath “Linyarath”.

My building-from-single-syllable-root-words approach was fun, but potentially problematic, as I started to realize that there was a distinct possibility I might use up all the available single-syllable combinations before I had enough roots from which to build an entire language—or at least it became increasingly difficult to narrow down which words were important and general enough that they should be the single-syllable bases from which the whole of the rest of the language would be formed. Of course, I never really got that far… I was, after all (judging from my printing-style and my use of erasable ink) only in Grade 7 or 8 when I did this.

I find it fascinating, now that I’m looking back on this from someone who became fascinated with the Japanese kanji (“Chinese” characters) much later on in life, that this combination of single root-syllables is actually the approach that the Japanese adopted when they began to formulate their own written language from Chinese-character loanwords—but their approach was generally to combine single syllable roots into pairs, and each syllable so combined had an additional semantic layer in the pictographic characters that they were appropriating, allowing for a much wider range of meaning. It’s also interesting, in retrospect, to realize that the Japanese character の (no) serves a function very similar to Linyarath’s “y”—especially given that I had absolutely no exposure to Japanese at this age. It is possible that the French “de” might have been a bit of an influence here.

Given that my world-building, at this point, was mostly in support of my and my brother’s extensive “let’s pretend” play, this did mean that there was an extensive component of collaborative storytelling built into my world-building from the beginning. And, with C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien’s deep stories and world-building looming ever larger in my adolescent mind, I began to form the desire to be a writer of fantasy, like they were. This meant starting to embody elements of my world in actual stories, starting with (of course!) a wiry red-haired young hero who would triumph not merely by force of arms, but by intelligence: Prince Keece. The name of my hero probably predates my development of Linyarath, as it obviously has no relation to the language, but it’s also possible that I ignored the language because its primary function was for the development of place-names—something that would work its way much deeper into my world-building some years later.

At the same time, perhaps influenced by Tolkien’s “long defeat” and the death of King Arthur, and undoubtedly influenced by the experience of my father’s defeat in his fight to retain traditional Judaeo-Christian values as the basis for discipline and the continued prioritization of the family in the BC school system, the stories I began to formulate (largely in my head) tended more and more towards valiant and glorious “last stands” of the sort that filled Reepicheep’s head, with the noble defense of the righteous cause against overwhelming odds becoming the core of the story of Arath.

The core story, which I’ve never actually written, was of Prince Keece (and his commoner friends that he’d made while venturing out of the castle in disguise) having to take over the rule of the Kingdom of Arath when his beloved father, the king, is killed in an earthquake—a disaster that also destroys large portions of the wall around their capital city. Sensing the kingdom’s weakness, an evil wizard raises an army that descends upon Arath, which Prince Keece and his friends, with their own hastily raised militia, hasten to meet. Unfortunately, Prince Keece and his friends are outmatched in the battle, as the wizard deploys a strange magic that results in Prince Keece and most of his army running wild and jumping off a nearby cliff into the sea, where they all presumably drown. The wizard and his army then capture the capital city largely unopposed and begin building a fleet to go on to capture the island at the end of the peninsula, to which the remnant of the citizens of Arath have fled.

However, as the wizard’s great fleet sets sail, it is set upon by a never-before-seen army of merpeople, who turn out to be Prince Keece and his friends and his army: the wizard’s magic made them unable to breathe air (which was why they instinctively threw themselves into the sea) and transformed them into merfolk who help the citizens of Arath defeat the wizard and his invasion fleet, and who ever after protect the island—and the entire nation of Arath, once the peninsula is retaken—from any attack over the sea. A noble and valiant last stand is thus turned into victory, as the transformed rightful king and his army arise from their watery “grave” to defeat evil forever.

That last sentence turns Prince Keece into much more of a Christ-figure than I ever intended—or, perhaps more accurately, much more of one than I ever actually realized. It seems to me, as I reflect now on these unfinished works of my youth, that the endeavour—besides being a natural outworking of the desire to emulate my two greatest heroes—was very much an attempt to make sense of the world through story and the co-requisite world-building.

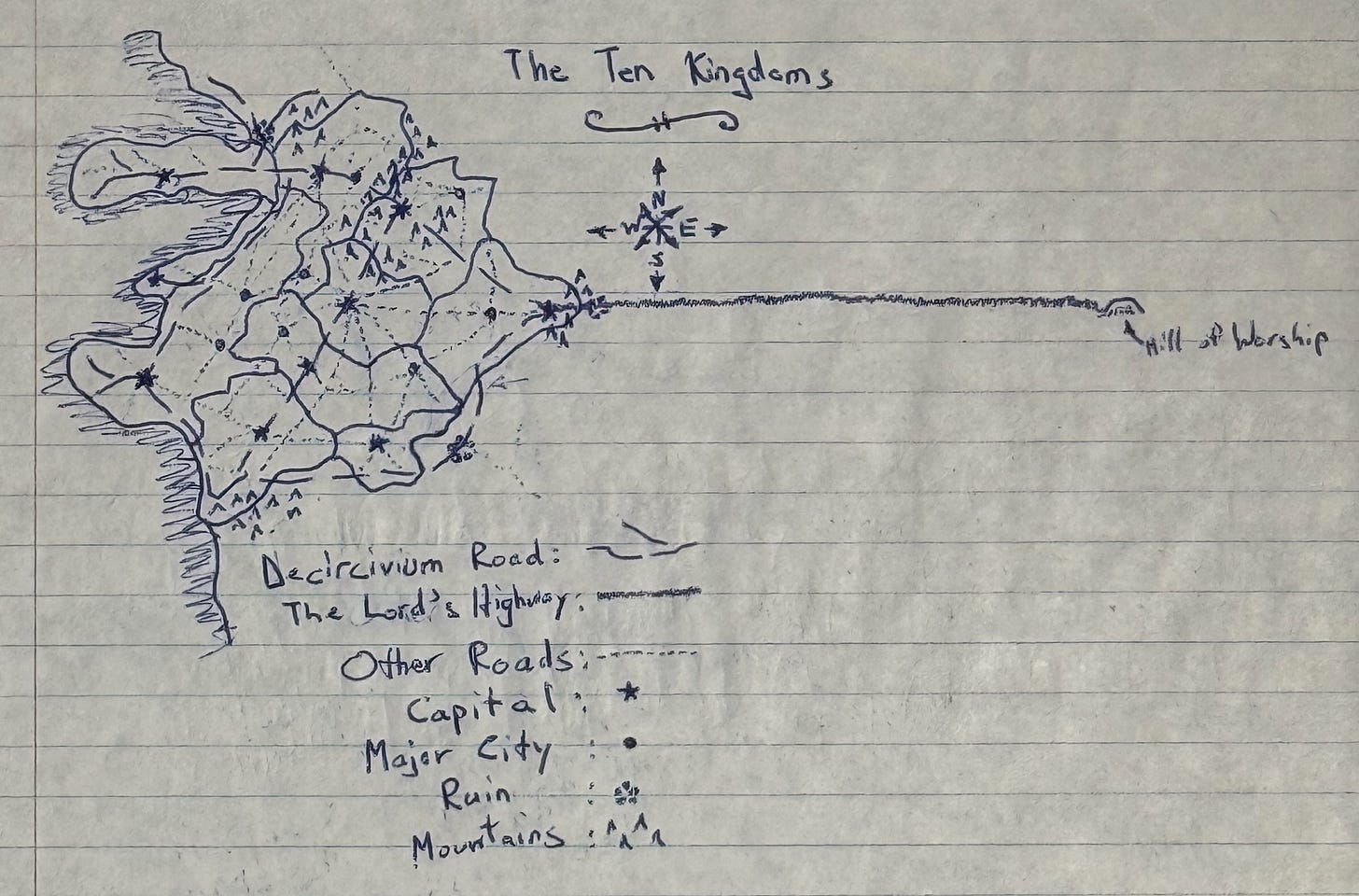

The natural role of world-building as an attempt to make sense of the world became much more obvious as I started to flesh out the world around Arath and its overall accompanying story. Other kingdoms and empires had always necessarily existed: after all, you can’t have a battle without an enemy! But I had never really thought much about the other countries or where they came from. My reflections here began, I think, in a separate story that contained an attempt to render the separate yet united nature of Protestant Christianity in fictional form as a backdrop for a quest-style adventure: a group of young representatives from various nations of a loose conglomeration of states called “The Ten Kingdoms” would all be travelling through dangerous territory to come together in a sort of pilgrimage to the Hill of Worship.

It was an overly sentimental premise which unsurprisingly turned into a rather tacky story, which I quickly abandoned, but the notion of kingdoms, nations, and cultures forming around common ideas and dividing over ideas they disagreed on had enough truth to it that it became the basis for my thinking about how the various nations that were the enemies of Arath might have formed. Moreover, the vision of The Ten Kingdoms as medeival-style Christian states divided by doctrinal differences but ultimately united with one another against the enemies around them really resonated with me: so much so that Arath became (temporarily) one of those ten states as The Ten Kingdoms worked their way into the world that I was coming to call—using the language of Arath—“Alathaa” (land-sea-air).

But now the problems of the unfinished “back story” of this world were starting to pile up. If there were Christians in this world—or, for that matter, humans—where did they come from? What was the connection between Alathaa and our own world? If there was transformation magic in the world of Alathaa that could be used by the wizards, what was it and where did it come from—and were there other hybrid races besides the merpeople, and, if so, what were their origin stories? If the connection between our world and Alathaa was something scientific rather than magical (which was what I was leaning towards at the time), how could Alathaa and Arath end up as a medieval world with swords and bows and arrows instead of guns? And I still hadn’t gotten around to populating or characterizing or establishing the origins of any of the other “enemy” nations. Building a world, it seemed, was turning out to be a rather complicated project!

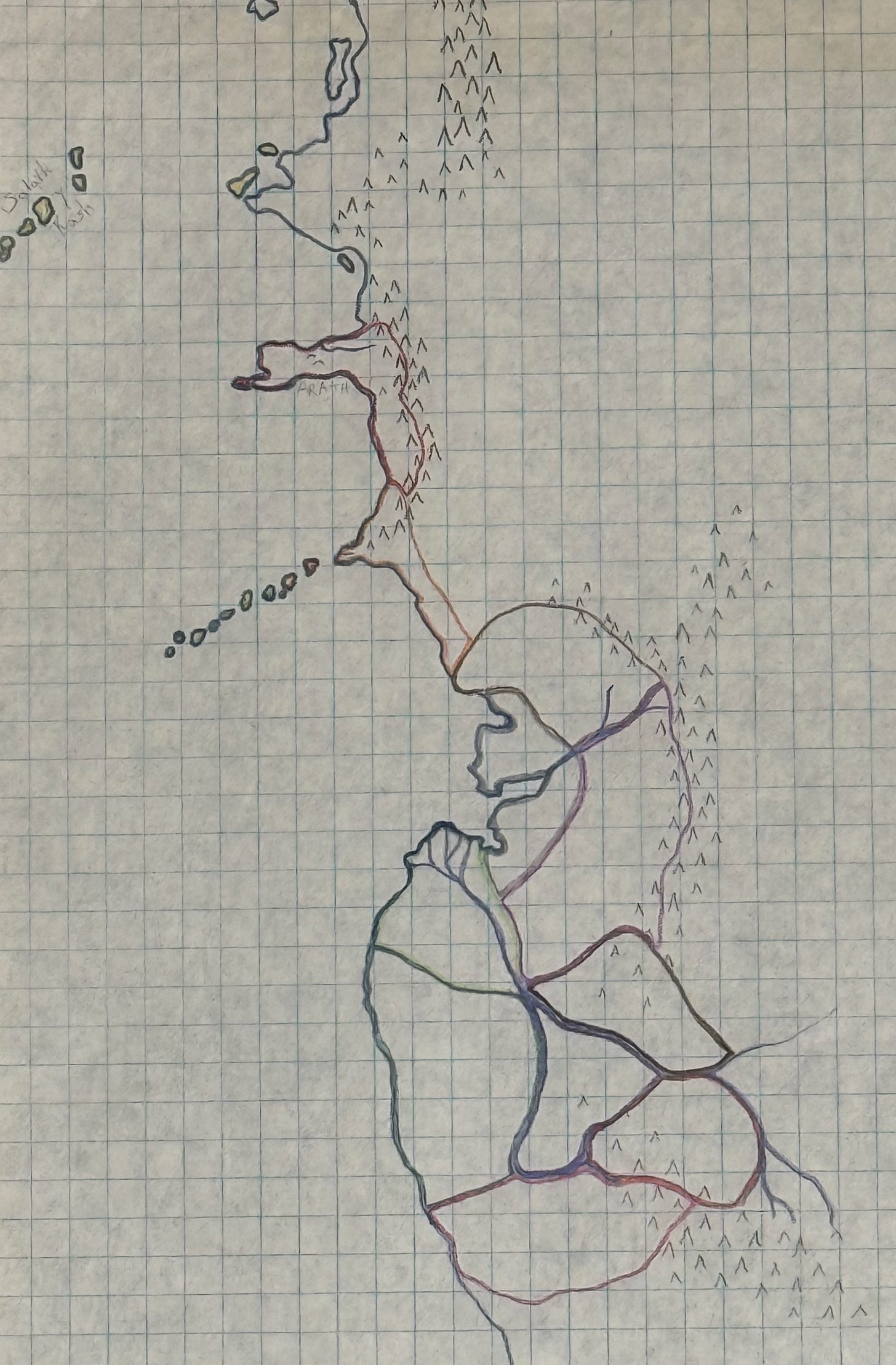

That I was starting to think more seriously and systematically about these problems can be seen in the increasing geographic realism of my map-making, whether that be the attempt to more accurately establish scale using graph paper (in the map above), or the somewhat more rationally arranged mountain ranges, tributaries, and river deltas in this more detailed map of Arath from about the same time period, below:

However, as a still rather young writer, I was really only just starting to think about how life, the universe, and everything worked together, leading to a fair number of false starts. The most significant of these was the idea of a Sci-Fi-inspired connection between a future earth and this fantasy world (quite possibly inspired by McCaffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern series), which initially took the form of a space expedition to a wormhole at the edge of our solar system. The expedition idea was eventually abandoned in favour of a much simpler portal to Alathaa that appears on Earth and is stable enough for long enough to allow the establishment of a colony on the unpopulated world of Alathaa. However, the world of Alathaa turns out to have energies and physical principles that are not quite compatible with those of Earth and, as the portal destablizes and disappears, the native Alathaan energies and physics reassert themselves. The Alathaan energies replace earthly electricity and turn out to be transformative, destroying the earth technology of the colony and thus scattering the tech-dependent colonists, while also transforming some of them into the first demi-humans (such as fauns and centaurs) and forming the foundation of future transformation magic.

The other important Earthly element that comes out of this disaster is the Codex: a last-minute printout of all available Earthly knowledge that is distributed amongst the scattering colonists as they spread out to establish themselves in scattered tribes throughout this vast new world. Each group ends up with only a part of the printout, though, so the ideas contained in each section, from works of literature to works like Das Capital, end up as the defining texts for each of the tribes, thereby forming the bases for all of Alathaa’s different countries and cultures.

The Christians, then, in Alathaa, were just Christians from Earth, who would naturally prioritize obtaining the Bible as their part of the Codex—and, of course, all the nations would trace some parts of their origins and ideas back to Old Earth, but those memories would eventually fade for most of them. The reversion to medieval technology would be the result of having no electricity and slightly different physics which, along with the loss of technical knowledge and maybe a bit of magical hand-waving, would also prevent the re-invention of gunpowder.

But then, for various reasons, despite having solved all the problems, I didn’t go on to write anything. Not the least of these reasons were my immaturity and my lack of discipline as a writer, but, besides these, it almost seems, in retrospect, that the main point of the project was not the stories I would write in the world, but the sorting out in my head of how the world worked—both my fantasy world and the real world that I myself was a part of.

In Part II, I plan to talk about how, in early adulthood, I actually wrote a short story which, while not initially part of the world of Alathaa, enters into it and transforms it, giving it a “final” mental shape which, once again, can be seen as an embodiment of my evolving understanding of the real world.

I have also added, as a sort of nonessential appendix, below, my childhood “The Black Knight” and “The Vikings” poems that I mentioned above (which I will probably write about in a completely separate post, someday…) and the very incomplete “Rules” for Linyarath.

The Black Knight

The knight rode onto the grassy field, With his lady’s scarf on his head. By the end of the day (or so he hoped), His opponent would be dead. Dark black in the sun his armour gleamed, Blood red the sword on his shield, Dark blue his lady’s scarf on his head, And dark green the grass on the field. Then suddenly a trumpet call Shattered the peaceful sound Of small birds singing in the air And crickets on the ground. A knight in silver armour Appeared on the dark green field, And they rushed at each other and then was heard The sound of wood on both shields. When both knights had splintered three lances, The battle continued on foot, Then the knight in silver armour Pierced through the armour of soot. Through neck-vein, spine, and helmet The trusty sword struck true, And set the lady weeping, The lady with scarf so blue. 1980/81

The Vikings

A man was walking by the shore (The wind was fairly strong) When he a ship espied afar, A Viking boat, quite long. Away he sped to warn the town, Soon up in arms were they. They lined themselves upon the beach, All ready for a fray. The Viking ship came swiftly on, And soon was on the beach; The Vikings stood upon the shore, Just out of longbow reach. “Send out your champion,” their captain roared, “That they may battle do!” And so they stood upon the sand, The two sides’ champions two. The Vikings’ man raised up his sword To give a mighty blow, Then darted in the townsman, And laid the Viking low. The Vikings gave a roar of fear, And started t’wards the ship, But the townsfolk intercepted, And stopped their little trip. All day and night the battle raged, And when the sun came up, There were no Vikings to be found: They all had given up. The townsmen were exultant; They praised their champion bold. Their champion lived a happy life, And lived to be quite old. May 9, 1982

“I was really only just starting to think about how life, the universe, and everything…” haha

Do you think, “…that is distributed amongst the scattering colonists as they spread out to establish themselves in scattered tribes throughout this vast new world.” Was inspired by the Tower of Babel?