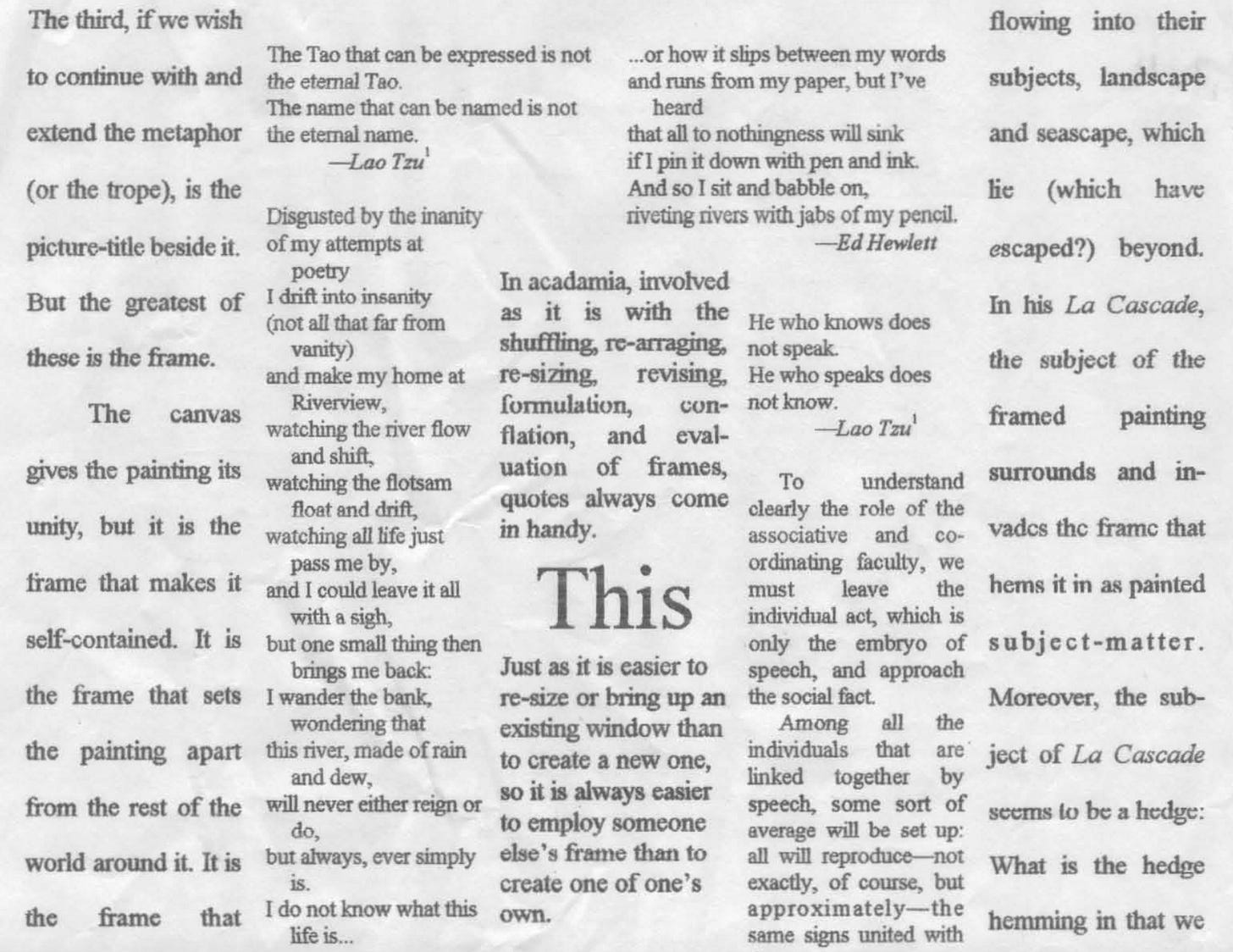

Many years ago, while I was a grad student at UBC taking a literary critical theory course, I wrote an essay responding to de Saussure and Foucault and Magritte which I entitled “This is Not a Frame—And Is”. The gist of it, if I can summarize such a complex intertextual endeavour in a single (or double) phrase, is that words are frames, and that “The Word [Logos] Is The Frame”, as I concluded. It might, perhaps, be more accurate to conclude that the Word is the uncontainable Image (that Magritte—or at least Foucault glossing Magritte—references, and perhaps worships as the “Unknown God” that the Apostle Paul identifies), but I still think my characterization of words as frames is particularly simple and helpful and accurate.

One of my parishioners, trying to draw together some of the disparate threads of my musings on “Technology, Wisdom, and the Word” and “AI, Identity, and Education”, as well as some ideas I mentioned with regards to human beings as makers of meaning (in the context of liturgical symbolism) and the continual swing of the cultural pendulum, asked if he could get my thoughts on the following:

Could it be that systems and systematization are ultimately inevitable? In that God created the natural world full of systems and regularity, and so even if we go all the way down to the level of anti-civilization and man living out in the wilderness, we still don't get away from systems. We simply replace one set of civilizational systems with another set of natural systems?

HOWEVER…Is another quality that makes us unique and essentially human, and is a thing that we humans do best, actually the ability to transcend and break free of systems? In that we have this spark of free will, where at any moment we have the potential to not follow a system and do something else, or also choose between different systems? And is this related to sacrifice, in the sense that the only way that we can behave in a way that is not systematic is through self-sacrifice, and not being led by our passions?

Being the silly person that I am, I am tempted to simply state as a single answer to all these questions, “Yes.” However, this thoughtful series of interrogative musings deserves a fuller answer, especially as he goes on to say,

I almost want to say something like, "We find ourselves in a world full of systems and rigid mechanisms (laws of physics, laws of the jungle, and so on), and on top of these we build even more systems (laws, formalities, customs, etc.), but in between all of these mechanisms is where our humanity lies, because that's where we do what machines cannot do, and what animals can only do to a very small degree (if at all), which is to not be mechanistic, and actually make choices."

There are a number of good ways to answer and/or riff on this (including, maybe “Yes”), but I’ll offer one that, as usual, draws on Tolkien, as well as on the “words are frames” observation noted above.

Human beings are indeed makers of meaning, but we’re actually not the best at making meaning: God is. We are in this regard, as in our storytelling, as Tolkien notes, really merely subcreators—and, as subcreators, we tend to be most successful when we imitate the work of our Creator. That’s why we find storytelling and systemic analysis so compelling.

Tangenting a bit here, I would note that these two most fruitful approaches to the making of meaning—or, perhaps more properly, to the sorting out what things truly mean and resultant assigning of meaning—are beautifully encapsulated in Plato’s and Aristotle’s respective approaches to philosophy. Plato insisted that the only way to really get at the meaning of things was through dialogue, so his philosophy takes place through the dramatic medium of telling a story about two or more people talking their way to the truth (i.e, a play), while Aristotle’s approach was to systematically analyze by categorizing (which strikes me as work). Tangenting even more, and more personally, if it comes down to choosing between play or work, I know which one I’d usually choose!

But we are subcreators, not creators ex nihilo, and our subcreations are necessarily always limited. Which is perhaps one reason why neither Plato nor Aristotle or their respective approaches have ever entirely prevailed over the other. But, given that these two subcreative approaches are our primary way of making sense of the world, the answer to the first question is yes, as far as we humans are concerned, systems and systemization are inevitable, in that they do simply mirror—or, more accurately, frame/summarize/represent the divinely created and sustained systems that comprise the reality which defines us, which we attempt to understand, and in which we participate.

HOWEVER… our attempts to systematize, explain, and understand are always necessarily limited. Words are merely frames, or, if you prefer (with de Saussure), arbitrary pointers to incredibly complex realities that can never be fully described or encompassed in something as limited as sounds and symbols. Yet the symbols somehow, for us humans, make really present at least some part of what they symbolize.

Take, for example, the word “table”. When I began reflecting on this question with my daughter, we were seated at a table, a large flat ovid-shaped structure made of wood which we use to raise things off the floor, generally to make reaching them more convenient and to keep the things set on them from getting dirty. This particular table was varnished, with some portions of the varnish mostly missing, some due simply to wear, others due to too-hot containers having been placed on it. But even this extended elaboration on the word “table” does not get at the molecular structure or composition of the wood of which the table is mostly comprised, nor the wood-working tools that were required to cut and shape the wood, nor the common and unpleasant experience of bumping up against sharp corners of wood that led to the stylistic choice of a rounded rectangle/ovoid shape that this table shares with many other modern tables, nor the sacramental aspect of “table” that we see in 1 Corinthians 10 in which every table participates… and this is still not complete.

Every use of the word “table” partakes of some or all of the above realities, or even more, yet is always essentially incomplete—and yet, the simple statement that I and my daughter were seated at a “table” as I began my reflection is also somehow more than sufficient.

Interestingly, I think this is all captured neatly in Genesis 2, where God, having created (and, of course, sustaining) the animals, brings them all to Adam to see what the first man would name (“frame”) them.

The essential problem with systems, then, is not the act of systemization itself, since that is part of our role as stewards and meaning-makers and understanders and sub-creators, and, as such, is actually an expression of our love and free will. The problem arises when we mistake the symbol for the thing itself, when we begin to think our stories and systems are complete, when we start to think of ourselves not as “gods” (as in, “Have I not called you ‘gods’?”: we are little ikons, made in His image) but as God.

This mistake is, in fact, the diabolical reality underlying the totalitarianism that is the false triumph of system common to both “right” and “left”—while the equally diabolical rejection of system in anarchy stems from its total rejection of the limiting and inadequate “word”. The path of truly human humility lies in the via media that recognizes both these realities: on the one hand, we are made in the Divine Image, subcreating with story, word, and system, while on the other, as creatures, our subcreations are only ever limited, symbolic abstractions that merely point to and frame portions of the divinely sustained Reality in which we ourselves are bound as dusty participants—and yet somehow, by the divine grace of the Word which unites our human nature to the Divine, our limited words are sufficient.

But also, in answer to the second question about which I have already waxed loquacious, yes, the exercise of our free will in acts of self-sacrificial love is that essential act of humilty and self-control which is at the root of our true experience of Reality, and, as we subcreate systems and stories that describe and decorate that Reality while recognizing both their beauty and their limitations, this is indeed where our humanity lies (over and above both the animals and AI): this is how we fulfill our royal priesthood, as limited “words”, offering up to God His Word: His own of His own, on behalf of all and for all.

Update: I had so much fun returning to my old essay in this post that I created a whole Geek Orthodox podcast episode telling the story of the role it played in helping me to see the truth in Orthodox Christianity—so, if you’re interested, go check that out, but do note that it’s a long (30-minute) story!

Thanks Father for this elucidation of systems. This helps put together a lot of what I've thought about systems in the context of software & organizational design at work!

The one theme I've always seen is the enormous gap between systems as conceived in thought or on paper, and the reality that we engage and participate in on the ground.

I've contemplated for a long time how to do truly excellent work – and for me it's all about discovering that match between system and reality through a magical trial/error process with the right amount of tolerance for adaptability.

One example in business may be the concept of the "org chart". It looks pretty on paper, but it doesn't match how the organization works in reality. If we followed the org chart strictly, and if people actually did what their job description said their job was, we would be overwhelmed with all the little responsibilities we didn't plan for, and so we'd not be able to get much done at all. The true org chart is much more nuanced, and yet more interesting and full.

I noticed it can be hard to differentiate true competency from theoretical competency, but when you find truly competent people there's this almost mystical confluence of theory and practice that to me is beautiful to see in action. It's annoying though that frauds can often climb the organizational ladder by faking being this truly competent person by using strong rhetorical skills!

A fraudulent strategist can clearly articulate a plan, but the true strategist has a deep ground connection and humility that allows him to generate real success. Usually the real ones are creative, artistic, and retain the spirit of the amateur (per the original etymological connotation).

I digress and must now make my way to church. Thanks again Father!

Thank you, Father. Very well put (eloquently framed)!