Saul, on his way to persecute the followers of Jesus Christ in the city of Damascus, sees a light from heaven which blinds him, and hears the voice of God saying, “Saul, Saul, why are you persecuting Me?” At which point Saul addresses God as any good Jew of his day would address God, calling Him “Lord”, and asks him, “Who are You, Lord?”

The answer that came to him, in a literal blinding flash of insight was, “I AM Jesus, whom you are persecuting. It is hard for you to kick against the pricks that are goading you towards Me.”

This is the mind-bending beginning of the Apostle Paul’s conversion, but not the end of it. It ends with Ananias being goaded into going to heal Saul, something like scales falling from Saul’s eyes, and Saul getting baptized.

But it begins with Saul’s mind being bent, his misconceptions about God being shattered, his becoming unable to see anything else, and, only after this event, and only after Saul’s enemy is convinced by God to act as his friend, Saul being healed and becoming able to see things as they actually are.

To convert to Christianity, one’s mind must be bent—or, maybe more accurately, unbent from whatever it is that is turning one’s mind inward upon itself.

I have experienced this and it has been my privilege, as an Orthodox priest in a small “mission” parish, to see this over and over again over the years.

This unbending takes many forms—as many as there are individuals, perhaps, but a few particularly resonate with me as they mirror my own experience.

Not too long ago (in relative terms), Paul (not the apostle), asked me, in Q&A, what it means, experientially, to believe. It was a mind-bending question that I realized, as soon as he asked it, that I’d never really considered before. And when I gave Paul my “This Is Not a Frame—And Is” essay, thinking that he’d be one of the few who might appreciate it, he “raised” me Gödel, Escher, Bach, which I’ve still only skimmed and scratched the surface of—at which point I realized just how fully his mind had been “bent” by his encounter with the Infinite, which is why, as it became “unbent”, he had to become a Christian.

Even more recently (today, in fact), Lucas wrote a Substack post in which he grapples with the Infinite and quotes the Indian philosopher and poet, Rabindranath Tagore. A couple of selections from a passage he quotes at length particularly struck me:

The man of science knows, in one aspect, that the world is not merely what it appears to be to our senses; he knows that earth and water are really the play of forces that manifest themselves to us as earth and water - how, we can but partially apprehend. Likewise the man who has his spiritual eyes open knows that the ultimate truth about earth and water lies in our apprehension of the eternal will which works in time and takes shape in the forces we realise under those aspects. This is not mere knowledge, as science is, but it is a preception of the soul by the soul. This does not lead us to power, as knowledge does, but it gives us joy, which is the product of the union of kindred things.

And, while Christianity goes one step further, understanding the Creator as transcending as well as immanent in His Creation (more on that in a moment) and naming Him by a different name, this too resonated:

The being who is in his essence the light and life of all, who is world-conscious, is Brahma. To feel all, to be conscious of everything, is his spirit. We are immersed in his consciousness body and soul. It is through his consciousness that the sun attracts the earth; it is through his consciousness that the light-waves are being transmitted from planet to planet.

I am not at all familiar with Indian thought, but I was reminded, by Lucas’ quote, of my initial encounter with Eastern thought in the Tao Te Ching: “The Tao which can be named is not the eternal Tao.” And then, much later in my journey, of Bishop Kallistos Ware’s The Orthodox Way:

“Thou hast brought us into being out of nothing” (The Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom). How are we to understand God’s relation to the world he has created? What is meant by this phrase “out of nothing”, ex nihilo? Why, indeed, did God create at all?

The words “out of nothing” signify, first and foremost, that God created the universe by an act of his free will. Nothing compelled him to create; he chose to do so. The world was not created unintentionally or out of necessity; it is not an automatic emanation or overflowing from God, but the consequency of divine choice.

If nothing compelled God to create, why then did he choose to do so? In so far as such a question admits of an answer, our reply must be: God’s motive in creation is his love. Rather than say that he created the universe out of nothing, we should say that he created it out of his own self, which is love. …

As the fruit of God’s free will and free love, the world is not necessary, not self-sufficient, but contingent and dependent. As created beings we can never be just ourselves alone; God is the core of our being, or we cease to exist. …

As creator, then, God is always at the heart of each thing, maintaining it in being. On the level of scientific inquiry, we discern certain processes or sequences of cause and effect. On the level of spiritual vision, which does not contradict science but looks beyond it, we discern everywhere the creative energies of God, upholding all that is, forming the innermost essence of all things. But, while present everywhere in the world, God is not to be identified with the world. As Christians we affirm not pantheism but “panentheism”. God is in all things yet also beyond and above all things. He is both “greater than the great” and “smaller than the small”. In the words of St. Gregory Palamas, “He is everywhere and nowhere, he is everything and nothing.”

Both of these mind-bending texts played a key role in my conversion to Orthodox Christianity: they were mind-bending encounters with the Infinite that eventually helped to unbend my mind, enabling me, ultimately, to begin to see the world as God intended me to see it.

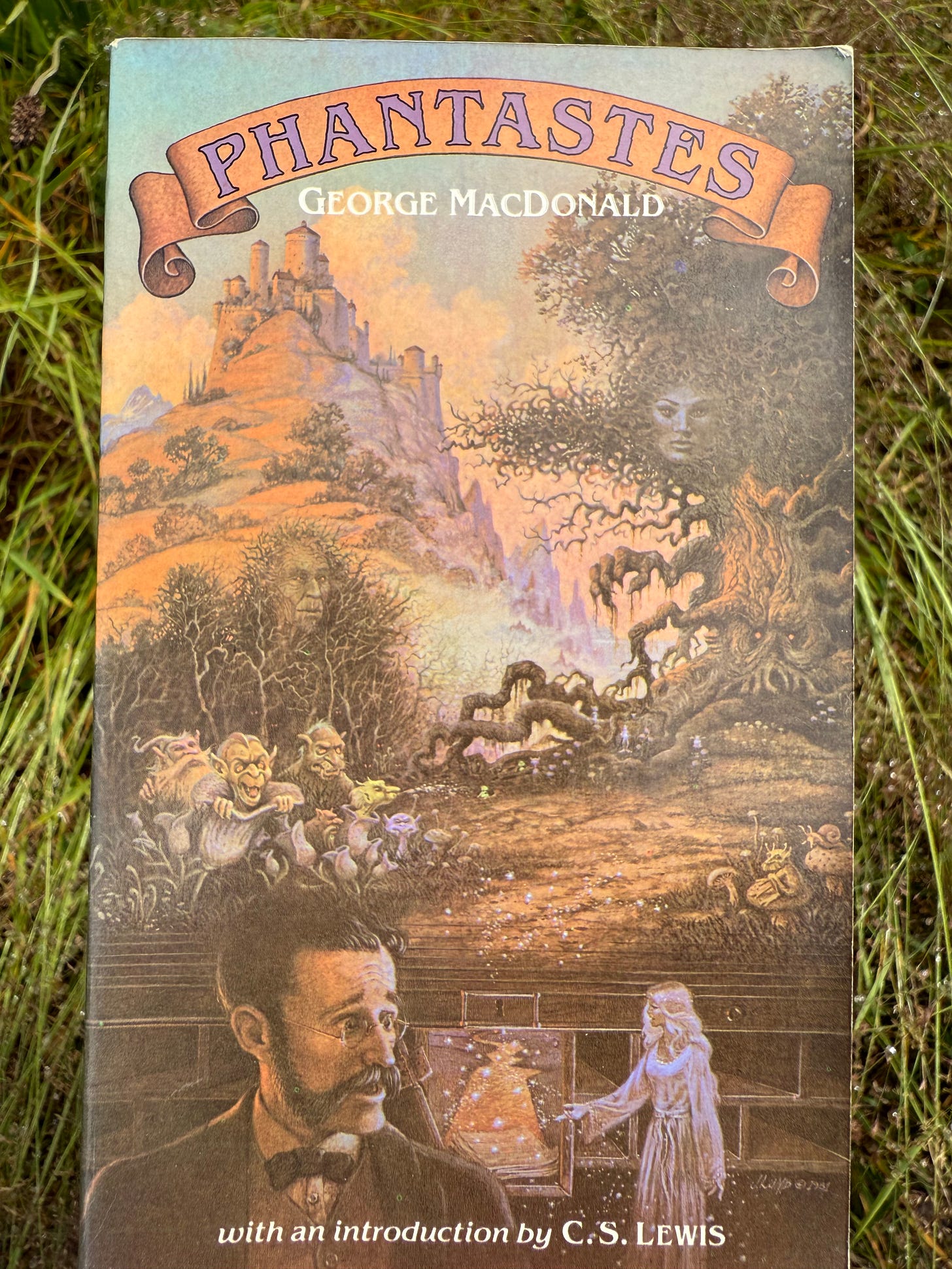

I suspect this bending and then unbending of the mind as one encounters God is universal, but may not always be perceived—or at least not understood for what it was until one approaches the end of the journey it initiates. Such, at least was C.S. Lewis’ experience, as he encountered Joy in George MacDonald’s Phantastes and describes it (in Surprised by Joy) as the initial “baptism” of his imagination:

It is as if I were carried sleeping across the frontier, or as if I had died in the old country and could never remember how I came alive in the new. For in one sense the new country was exactly like the old. I met there all that had already charmed me in Malory, Spenser, Morris, and Yeats. But in another sense all was changed. I did not yet know (and I was long in learning) the name of the new quality, the bright shadow, that rested on the travels of Anodos. I do now. It was Holiness. For the first time the song of the sirens sounded like the voice of my mother or my nurse. Here were old wives’ tales; there was nothing to be proud of in enjoying them. It was as though the voice which had called to me from the world's end were now speaking at my side. It was with me in the room, or in my own body, or behind me. If it had once eluded me by its distance, it now eluded me by proximity—something too near to see, too plain to be understood, on this side of knowledge. It seemed to have been always with me; if I could ever have turned my head quick enough I should have seized it. Now for the first time I felt that it was out of reach not because of something I could not do but because of something I could not stop doing. If I could only leave off, let go, unmake myself, it would be there. Meanwhile, in this new region all the confusions that had hitherto perplexed my search for Joy were disarmed. There was no temptation to confuse the scenes of the tale with the light that rested upon them, or to suppose that they were put forward as realities, or even to dream that if they had been realities and I could reach the woods where Anodos journeyed I should thereby come a step nearer to my desire. Yet, at the same time, never had the wind of Joy blowing through any story been less separable from the story itself. Where the god and the idolon were most nearly one there was least danger of confounding them. Thus, when the great moments came I did not break away from the woods and cottages that I read of to seek some bodiless light shining beyond them, but gradually, with a swelling continuity (like the sun at mid-morning burning through a fog) I found the light shining on those woods and cottages, and then on my own past life, and on the quiet room where I sat and on my old teacher where he nodded above his little Tacitus. For I now perceived that while the air of the new region made all my erotic and magical perversions of Joy look like sordid trumpery, it had no such disenchanting power over the bread upon the table or the coals in the grate. That was the marvel. Up till now each visitation of Joy had left the common world momentarily a desert—“The first touch of the earth went nigh to kill”. Even when real clouds or trees had been the material of the vision, they had been so only by reminding me of another world; and I did not like the return to ours. But now I saw the bright shadow coming out of the book into the real world and resting there, transforming all common things and yet itself unchanged. Or, more accurately, I saw the common things drawn into the bright shadow. Unde hoc mihi? In the depth of my disgraces, in the then invincible ignorance of my intellect, all this was given me without asking, even without consent. That night my imagination was, in a certain sense, baptised; the rest of me, not unnaturally, took longer.

I am—as we all are, really—only a pseudo-intellectual, a derived and artificial intelligence, a child playing with seashells on the shore of the unfathomable sea. But if I understand this phenomenon correctly, I think it may actually help to resolve the age-old Western Christian dilemma of God’s sovereignty and man’s free will; our illumination in this process is simultaneously voluntary and involuntary: once you see something as great as the Divine Infinite, you cannot unsee it, but what we do with what we see is our decision—and the only way to Heaven and not back to our self-centred Hell after we have seen Him is to lovingly and creatively and voluntarily bow down to worship and embrace the Divine Infinite who created and loves and sustains us and give us, in His image, our free will.

And this encounter with God, this bending to ultimately unbend, blinding to see without scales, is still really only the start of the eternal journey. As the once-blinded Apostle Paul says at the end of his famous chapter on Love:

For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.

If the unbending of our mind produces faith in God, the revelation of who He is produces hope, both of which are fulfilled and made perfect in Him who is Love.