Learning from Granddad

About occasional poetry and disagreement

My granddad had a poetry quotation for every occasion, and, when he didn’t, he’d write his own poem for it.

I’ve been wanting to share some more of my granddad’s writing for a while now, but the box that contains most of his poetry is safely stored on the top shelf of my mother’s closet, and I’ve been somewhat lax in visiting her this summer. Fortunately, with the start of the school year, my mother has taken to inviting us over to ply us with her home-cooked meals again, so I got another chance (after catching up with Mom) to collect some of his writings again. Here, then, are two pieces of his that I’ve been wanting to share, followed by a couple more of his poems that are too wonderful not to share.

The Little Red Schoolhouse

I’ve been wanting, since reading ’s “The One-Room Schoolhouse: How bad was it?” to share this short piece that my granddad wrote about his experience of “The Little Red Schoolhouse”. It doesn’t relate much in the way of the formal education he received there (which he finished in Grade Three), but it’s a great little reminiscence about his experience of being a very junior assistant janitor there!

It was a cold, blizzardy morning as my brother (Art) and I made our way along the page-wire fence toward the Little Red Schoolhouse. The thermometer had dropped nearly to zero (Fahrenheit), which to us boys seemed cold enough as we trudged through the drifting snow across the exposed flat where there was nothing to shelter us from the biting wind. It was our first winter in the Okanagan and we were not quite prepared, having been accustomed to the more moderate winters of the Pacific coast, and before that, of southern England. Our rubbers had not yet arrived from Eaton’s; but with our boots wrapped in strips of gunny-sack our feet did not suffer too badly on the mile-and-a-half hike to school.

It was necessary that we get to the schoolhouse some little time before the others, as my brother Arthur, who was thirteen, and two years older than I, was the janitor. He had undertaken to have the fire lit and the schoolroom warmed up each morning before the teacher and the rest of the pupils arrived; also to sweep the room each day after school. It was a one-room school. For this responsible undertaking he was to receive two-dollars-and-a-half each month, which he shared with me as his assistant. We usually got away with a good start in the morning; Mother saw to that, and if the drifts were not too deep and the sack-cloth wrappings remained fastened we managed to have the schoolroom fairly warm by class time.

But this was a bitter morning! The wind swept from its hideout in the northwest with malicious glee, literally shrieking through the wires of the fence where the imprisoned mustard and tumbleweed acted as a slight check to its otherwise unrestrained tantrums! The driven snow, a helpless victim to the wind’s mad caprices, managed here in some measure to escape its grasp and it settled on the leeward side of the fence in growing drifts, which made progress difficult. The gunny-sack wrappings on our feet seemed determined to come off. Perhaps it was breaking the trail through the drifts which loosened their fastenings, and our numb fingers could not secure them properly again. Finally we reached the schoolhouse door; two cold boys! My brother fumbled for the key… we were inside, sheltered at last from those driving particles and the biting wind!

Pitch pine kindling and dry wood were ready for the box-heater, having been prepared the previous day, and after clapping our arms vigorously about our bodies to quicken the blood-flow to our fingers and toes, we kindled a roaring fire which puffed and panted like a steam locomotive going up-grade! The lid of the air-tight heater threatened to blow off, but having learned something of its complicated mechanism we were able to keep it in check by dexterous adjustment of the draft and damper.

Placing our chilled (if not frozen) lunch where it would warm up with the room, we proceeded to unwind the frozen wrappings about our boots, stripping to the inner socks to give the chilled feet a chance for a quick come-back. Those were the days! Perhaps we did not learn much at those improvised desks from a purely academic point of view; but I think there must have been lessons learned that are missed now.

The War Poem

I’m a little hesitant to share this one. Would Granddad have wanted it published? It’s very personal, written on the occasion of the death of someone very close to him that he chose to identify in the title only as “S. J. H.” I’ve decided that I won’t go further than Granddad did in identifying the person whose death occasioned the poem, although any diligent reader and researcher may well be able to figure out who he was writing about.

Also, because it’s so personal, the poem is very much open to misunderstanding. Some context is necessary. But I think, with that context, it’s worth reading, as it embodies what Faulkner is said to have said about writing in his 1950 Nobel Prize acceptance speech:

The only thing worth writing about is the human heart in conflict with itself.

Faulkner actually said something slightly different, with a lot more nuance in the speech, which I’ll get to, but this poem very clearly captures my granddad’s heart in conflict with itself.

My granddad was Plymouth Brethren, who were kind of the original “evangelical” Christians (at least in the sense that the movement pioneered a lot of what we now see in “Evangelicalism”). One of the common views in the movement, which my granddad shared, was that once someone recognizes their sinfulness and turns to Jesus as their Saviour, they enter into eternal life, which, being eternal, cannot be lost: “once saved, always saved.” This belief obviously came into conflict with some pretty difficult and often ugly realities when those who professed to be Christians in their youth (as SJH did) went through horrific experiences such as World War I, which could destroy faith and severely disrupt their subsequent lives and families. This was the reality that Granddad was struggling with on the occasion of SJH’s death.

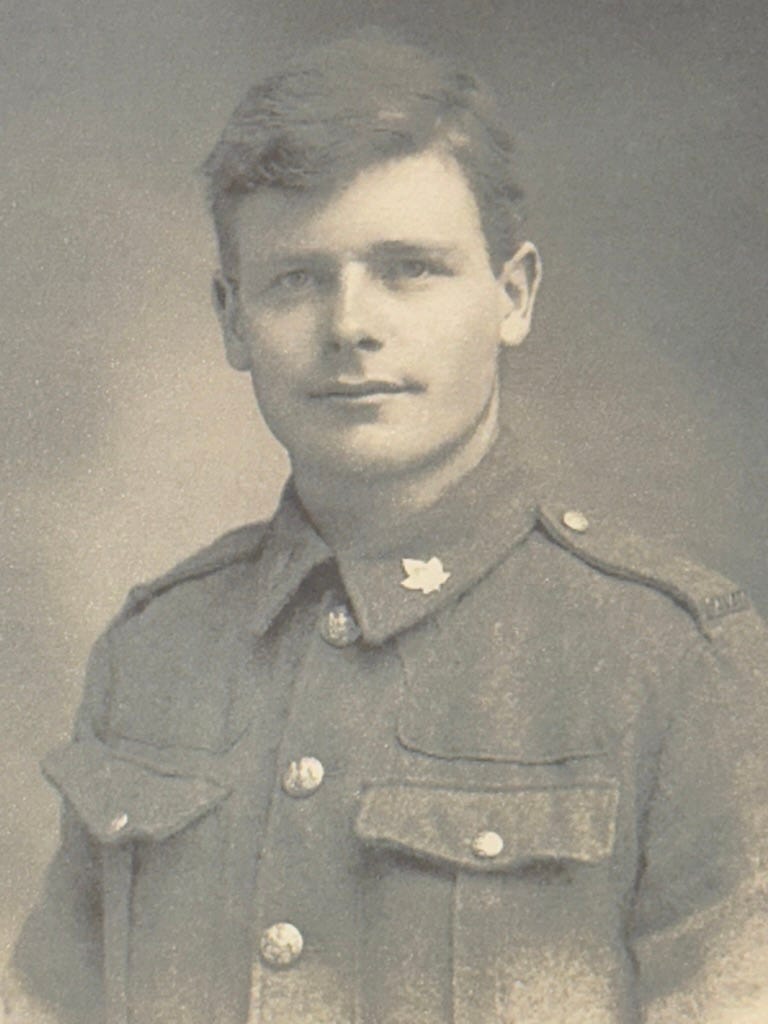

My grandad also had a complex attitude towards war. He signed up to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force near the end of World War I, in 1917, after he turned 18, his older brothers having already joined much earlier. He was placed in the Forestry Depot (possibly because of his youth) and spent most of his time behind the front lines, cutting wood for the trenches. He didn’t talk about his experience of the war much: I only remember one time when he mentioned how some of the trees they cut for the trenches would have shrapnel embedded in them, and how he had come across a downed German airplane on a rail-car and had cut off and taken a piece of its wing-fabric (the Iron Cross, I think) as a souvenir.

His older brothers, however, did fight on the front lines, and experienced in full the visceral tragedy that was World War I. From them, and possibly from other experiences, and certainly from his reading of literature, Granddad knew of the horrors of war, and was fond of quoting from Southey’s brilliantly ironic poem, “The Battle of Blenheim”, worth reading in full, but aptly recapitulated in its last stanza, of which Granddad would often quote the last line:

"And everybody praised the Duke

Who this great fight did win."

"But what good came of it at last?"

Quoth little Peterkin.

"Why that I cannot tell," said he,

"But 'twas a famous victory."

At the same time, despite his later pacifist preferences (he helped a friend register as a conscientious objector in World War II), he would not have been among those who “Declare glory and honour with war / Incompatible.” It was from him I learned to love Tennyson’s “The Charge of the Light Brigade” and “The Revenge: A Ballad of the Fleet”, and the inspiration for the goriest line of my youthful “The Black Knight” poem came from his reading to me Macaulay’s “Horatius at the Bridge”. He recognized that death in battle, while terrible and often pointless in worldly terms, was not the worst fate that could befall a man.

My granddad was also one of the most generous-hearted men that I’ve known, apart from my father (who thus came by his own generosity “honestly”), and this generosity of spirit came from his understanding of the love and the mercy of God. He was also humble, recognizing the limitations of his understanding and his beliefs, especially in relation to the infinite wisdom of God.

All this, then, is the context for this poem, in which my granddad is wrestling with the meaning of SJH’s death, not in battle, but after a long and seemingly fruitless struggle with life after the war.

S. J. H. [Nov. 7th, 1945]

Amid the darkness of the night I pondered and I looked for light. Oh Thou who doest all things well, Why thus? Why not a German shell? Why not the Somme's red battle blast, Or Ypres' furious holocaust? Than tragic death 'twere easier far To lose a loved one in the war. (To reason thus I have no right, But help, dear Lord, and give me light.) Thou know'st the times he looked to Thee From fearful straits that death might free! Yet death by day and death by night With piercing vision watched to smite! By shrapnel blast and raking fire Death searched the trench and shell-churned mire! Nor searched in vain --- his comrades fall, But Thou wast round him as a wall. Thou know'st the hours like years he spent In Ypres' awful salient, When concrete bastion ribbed with steel 'Neath thund'ring barrage seemed to reel! Piled corpses screen from with'ring fire, Grim parapets of blood and mire! Then death were transport -- glad release! From awful strife to deepest peace. From shell-fire's blast and fearful strain, Which tears and maims both flesh and brain! From scenes which baffle tongue to tell, From blood and carnage, earthly hell! A gate-way then might death afford To one who'd trusted in the Lord, A passage for the soul's free flight, To realms of bliss and Heav'nly light! To rest, to joy, and holy calm Where love Divine's the spirit's balm. For Thou didst draw him by Thy truth In years of tenderness and youth; He saw the Saviour in his stead A victim to the altar led. His guilt he owned and then could see That Jesus died to set him free. While raged those storms of fire and steel, When death's cold touch the soul could feel! (Though welcome yet a thing to dread, It shrank in fear but blessed the dead.) Lord did he know that by his side Thou walkest o'er the battle-tide? And could'st Thou look beyond and see Those fruitless years of vanity, Yet bring him safely through the strife, By thirty years prolong his life? Thy depth of wisdom who has found? A deep our plummets cannot sound! No fruit to Thee would I infer? But unbelief is sure to err. Though it is true, one could not say, He bore it in the usual way; Yet such Thy love and sovereign grace Thou would'st find fruit where none had place. And even though unto his own He failed to make the gospel known; Yet still Thou'dst bless -- Thou claimest one, Through others Thou has reached his son. And who can tell but he might be A means to reach the other three. Ah, God and Father Thou art wise Thou seest not with mortal eyes. Thy thoughts are as the Heav'ns in height, And like Thyself they're infinite. Ours are finite, moulded too By a dim, obstructed view. I gladly own that Thy design Were better far than his or mine. Our feeble eyes may not behold In pattern dark the thread of gold; But woven with the hand of love We'll trace it in the light above. For if we're Thine we surely know, (Revealed to Baalam long ago, Beholding when Thou could'st not see In Israel iniquity!) We know a seven-fold sacrifice Hides our perverseness from Thine eyes. We know, blest Lord, Thou dost not change, Our thoughts and ways to ill may range, And feet may stray on doubtful quest Which yester-year Thy foot-prints prest. We stumble but can never fall; The gift of life's beyond recall. His sorrows, we believe, are o'er, Salvation's joy Thou'dst thus restore. Taken Lord to Thee in grace, In righteousness to see Thy face: Thy likeness shall the mortal hide, Then will his soul be satisfied!

It is interesting, I think, to compare and contrast my granddad’s musings here with Faulkner’s full Nobel Prize speech, delivered five years later. They are very different musings, of course, one private and one very public, one in poetry, the other in prose but highly praising poetry, and both written very much under the shadow of war. Faulkner begins his speech by lamenting the tragedy of the spirit-crushing fear inspired by the threat of imminent nuclear annihilation.

Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.

This, of course, is the source of the paraphrased quote given above. He goes on:

He must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid; and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the old universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed – love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Until he does so, he labors under a curse. He writes not of love but of lust, of defeats in which nobody loses anything of value, of victories without hope and, worst of all, without pity or compassion. His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands.

Here, I think, Faulkner and Granddad are very much in agreement: there is something greater, something eternal, that we must strive and live for, to lose which destroys life itself by stripping it of hope and of love.

Until he relearns these things, he will write as though he stood among and watched the end of man. I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal simply because he will endure: that when the last dingdong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock hanging tideless in the last red and dying evening, that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking.

This is brilliant. I don’t think Granddad would or even could have gone here, but Faulkner is asking what the point of immortality is. It’s a good question. It is not enough merely to endure: eternal life, as Granddad himself would say, is not merely a matter of quantity, but, rather, quality.

I refuse to accept this. I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer’s, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet’s voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail.

Here, with Faulkner’s conclusion, Grandad again would be very much in agreement. He used, in fact, to argue with my mother that people should only read Scripture and poetry, not fictional prose, which Mom felt was wildly inconsistent (and with which, I’m sure, Faulkner would also vehemently disagree), but Granddad felt there was something about poetry which elevated it above prose—an access to deeper and higher spiritual truths, perhaps, and maybe also an ability to inspire—that placed it almost on the level of Scripture.

Poetry inspired Granddad. It moved his generous-hearted spirit. It was the means by which he worked out his own internal contradictions in the light of the Scriptures and the goodness of God. Poetry, for Granddad, was the ultimate expression of that human “spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance”, which helps “man endure by lifting his heart” and by “reminding him of the courage and honour and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past”—virtues which, in Granddad’s understanding, were rooted and grounded in God and thus, in Him, are the foundation of our ultimate future.

Those who know me will, of course, know that I disagree with my granddad, both on his views on fictional prose and on his belief in “eternal security”. But it is the height of folly to write someone off just because you disagree with them on something, even something important: when we do so, we lose the ability to learn from them. My granddad was generous-hearted and compassionate, a man who wrestled deeply with the tenets of his own faith when they were challenged by reality, a man who had the humility to recognize the limitations of his own understanding and the faith to understand that the seeming contradictions he was not able to reconcile, given his limited understanding, must be ultimately resolved in God’s divine love. One can learn from such a man, even when he may be partly wrong, if you love him.

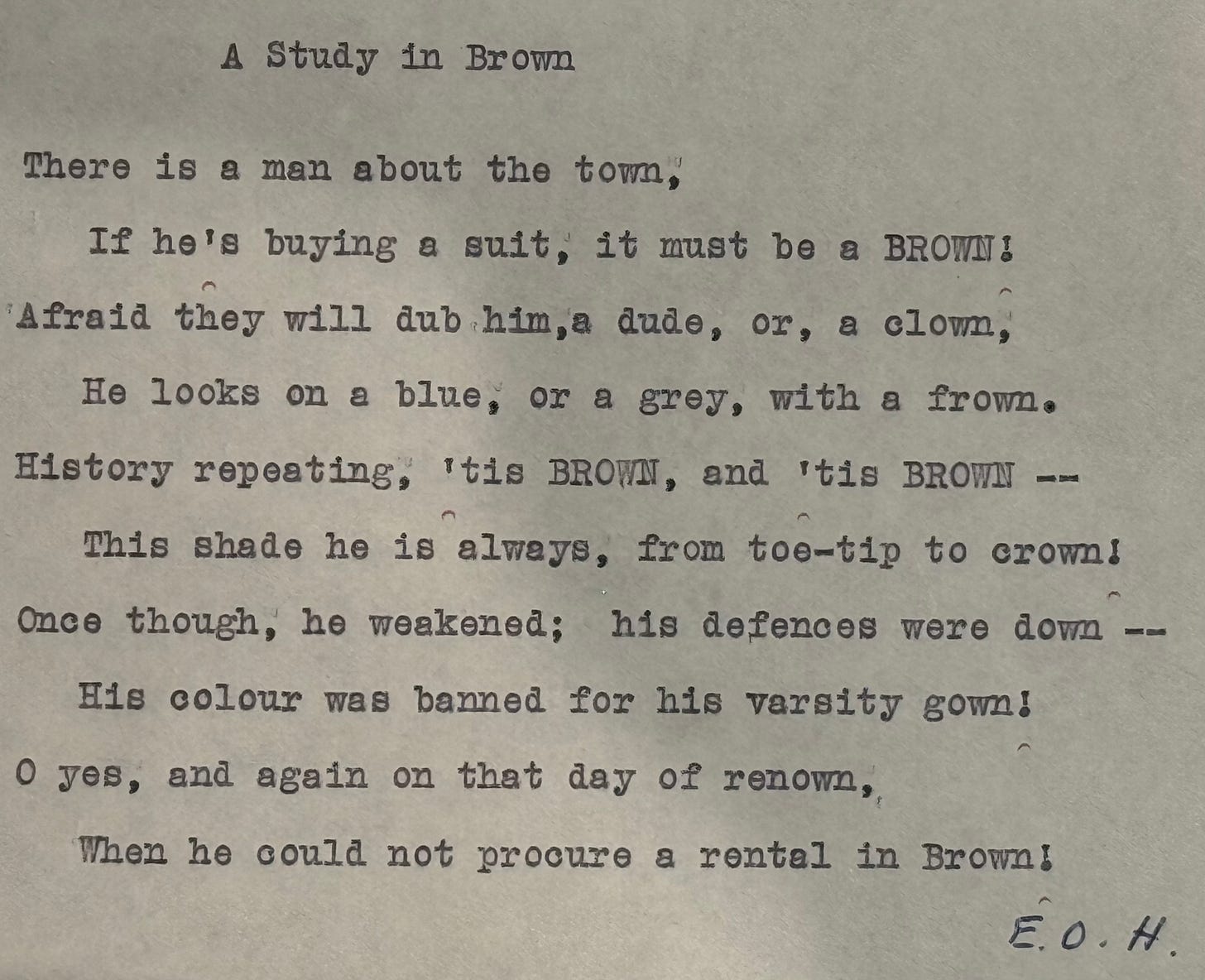

A Study in Brown

Changing the tone a bit, here is a more Dr. Seussian-style poem that my granddad seems to have written about my father (who very much had a preference for brown suits and clothing when I knew him!) on the occasion of my father’s graduation—I assume from university, when he obtained his Master’s degree, but it could have been earlier.

A Study in Brown

There is a man about the town,

If he's buying a suit, it must be a BROWN!

Afraid they will dub him a dude or a clown,

He looks on a blue, or a grey, with a frown.

History repeating, 'tis BROWN, and 'tis BROWN --

This shade he is always, from toe-tip to crown!

Once though, he weakened; his defences were down --

His colour was banned for his varsity gown!

O yes, and again on that day of renown,

When he could not procure a rental in Brown!

I cannot help but think here of my own poem in which I reuse the same rhyme as often as possible—in the first stanza deliberately and literally as often as possible—as I attempted to wrestle with the problem my professor posed to us when he noted that one of the most important subjects of poetry, love, has, in English, some of the fewest possible rhymes for the word!

A Love Poem, and The Cultural Cause Hyptothesis

A Love Poem In English, as I'll briefly prove, there's little that true-rhymes with love, unless one dwells upon her glove, or how she's gentle as a dove, or writes unto "My Lady of...", or gives his girl a gentle shove, he'll search from Hell to Heav'n above and not find more to rhyme with love. The Cultural Cause Hypothesis Perhaps it's like the English, then, those duty-bound, insensate men, to let love fester in a fen of worn clichés. Ironic, when one thinks how love has fed the pen of every poet, now and then, and verse and free, from West to Zen.

Rhymes are fun! And frustrating—which can be fun.

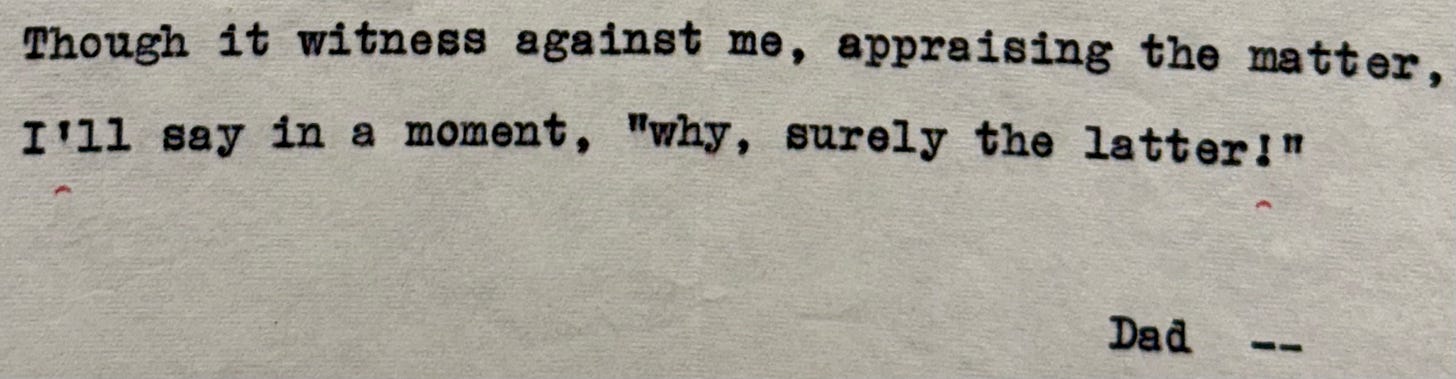

“They That Hear the Word of God and Do It”

This last poem of Granddad’s that I want to share in this post is maybe not one of his best, but one which I think, in context, reveals a lot about the quality of his character. Again, though, because it’s a deeply personal poem, it does require some contextualization.

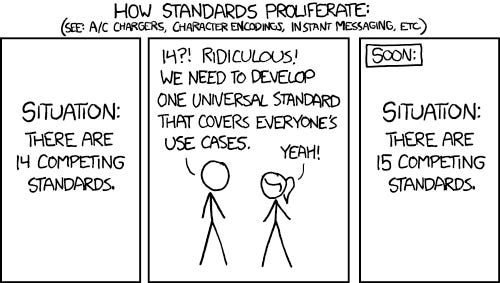

My granddad and his wife were both Plymouth Brethren. The “Plymouth Brethren” would actually never have called themselves by that name, since the movement (as they preferred to call it) was an attempt to transcend the denominationalism of the day by eschewing all names and statements of faith except what was actually in the Bible. They would simply have called themselves Christians or “brethren” (with a small “b”, since it’s a term Christians used to refer to themselves in the Bible), but, of course, this attempt to transcend denominational divisions inevitably devolved, in practice, into yet another denomination. (This is, of course, a universal and deeply human problem, as can be seen in the classic xkcd comic, “Standards”.)

Within the first generation, the Plymouth Brethren movement split into two main groups over the question of how to maintain some sort of consistency of church discipline while also maintaining the independence of the individual “assembly” (the movement’s preferred term for a local church). One group, dubbed the “Exclusive Brethren” followed the teachings of one of the most influential founders of the movement, J.N. Darby, who, although he thought the unity of the body of Christ was irretrivably broken, taught that it was still necessary for assemblies to act “on the ground of the One Body”—that is, the various assemblies should attempt to exercise church discipline (excommunication) in a manner that would be consistent around the world. The other group, dubbed the “Open Brethren”, emphasized that the independence of the individual assembly was paramount, taking precedence even over consistency of church discipline.

The “Open Brethren” themselves then split (mostly in North America) over the question of how best to prevent their openness from devolving into some sort of spiritual free-for-all, with the “Conservative” Brethren requiring a letter of commendation from another approved assembly before they would allow a Christian to partake of the Lord’s Supper (communion ) with them, while the rest of the “Open Brethren” (as we called ourselves) would generally allow any professing Christian to participate. I grew up in this latter group, for reasons that go back to my granddad and my grandma and my father, and which will bring us back to the poem.

My granddad was Exclusive Brethren and my grandma was Conservative. I gather that, when they got married, each assumed the other would eventually see the error of their ways and switch groups, but neither of them did, so they actually never went to church together. My father, not wanting to choose between his mother or his father, chose to attend an Open Brethren assembly when he grew up, which then became the assembly that I grew up in. This was naturally a source of some contention between my father and his father, my granddad, which I believe is what this poem is about.

I say “I believe” because neither my father nor my granddad are around to consult about the meaning of the poem, but I’m pretty sure I’ve reconstructed the meaning and the occasion of the poem rightly when I say that this poem

must have been occasioned by a remark made by my father about how his father, my granddad, was “a thousand times” a better person than he was, and

fits perfectly if we assume that Granddad is applying the “death-dealing letter” comment to himself and his chosen group’s legalism, and then contrasting it with my father and his chosen group’s far more “open” position.

"They That Hear The Word Of God, And Do It"

To say I'm a thousand times better than you, May be classified "humble", but hardly as "true". Where now is your logic? For which is the better, The one who adheres to the "death-dealing letter", Cuts off, and condemns every Christian on earth, Is missing the Spirit, and blind to His worth! Or, the one recognizing the gist of the Word, Who, regardless of failure, in spirit is stirred, Freely to meet with each sister and brother, Where the Heavenly birth he discerns in the other? The one who is legal -- in fetters is bound! Or, the one who is free, whose spirit has found What Godward is pleasing, and seeks to fulfill; Rightly discerning his Lord's blessed will? Though it witness against me, appraising the matter, I'll say in a moment, "why, surely the latter!"

What deeply moves me, as I read this, is my granddad’s obvious humility in this matter which was nevertheless important enough to him that he never went to church with his wife. In fact, I know from his diaries that, later in life, he would drive his wife to her assembly on Sundays and then just go home and pray and meditate on the Scriptures because it was not possible to get from his wife’s assembly to his own in time to attend the service. I believe that it also deeply moved my father because it seems fairly clear that he typed and treasured this poem: on the typewritten copy that I have, the attribution of authorship is not the usual E.O.H. (my granddad’s initials, which my dad would type or even write in), but rather, simply, “Dad”.

Learning from Granddad

I’ve written already about how I think we can learn from my granddad and his generation’s use of occasional poetry and apply it in our time. I’ve written also about how I think this approach can and should be applied more widely to produce a more personal and deeply communicative approach to art and communication in this age of AI.

Here, I think, the greatest lesson to be drawn is one which I also saw in my Mennonite grandmother. When she was younger and my Mennonite mother was intending to marry my English father, her comment was that the only worse thing she could do was marry a Frenchman! But she warmed to my father and, by the time of her death, surrounded as she was by children and grandchildren dealing with levels of difference and brokenness that far eclipsed the dangers she had worried about when my mother was thinking of marrying my non-Mennonite father (and having also seen another very successful and loving marriage when her son eventually married a French woman), her approach was simply to humbly and mostly silently disagree, when it was necessary, while continuing in a relationship of love.

My granddad was, of course, not perfect (as none of us are!) and he had strong opinions and beliefs that he expressed and lived out as consistently as he could. He disagreed with others, but, in those disagreements, he never wrote off or dismissed the complex human beings involved. Instead, he remained open to having those beliefs challenged and deepened and even corrected by the complex realities of human experience, and he engaged with and worked out and mulled over them in the deepest sources of Truth he had come to recognize: poetry and the Scriptures. And he brought those sources of Truth to bear on his relationships with those he loved in the humblest and most inspiring ways that he was able to: by quoting and reading and sharing and even—in the case of poems—creating them, as offerings and enactments of love.