I have been richly blessed, in my life, with mentors. From my father, who taught me to read before I went to Kindergarten (I still remember the flash-card for “car” which he made using hole-punch reinforcement rings for the tires), and who supplied me with a whole wall-full of books and more to foster and in support of my love of reading; to my grandfather, whose love of poetry I have already documented; to Dave Shields, my Grade 6/7 teacher who sports-narrated my exploits on the soccer field as the “Crusher” and just generally encouraged me to become the unique person and lover of literature whom I was already becoming; to Mr. Peter Sawatzky, whose TRS-80 Model I and Osborne computers were highlights of my experience of the first MEI Computer Club and whose laid-back teaching style in Computer Science helped me to rediscover my passion for teaching as an informal in-class peer tutor; to Professor Lee Milford Johnson (“the lesser doctor Johnson,” as he sometimes called himself), in whose honour I need to interrupt this list to break into poetry.

On My Professor’s Passing

He’d plunk his poetry upon the desk And, scrawling starlight-white across the green, Illuminate the rhythms arabesque Or zephyristic, raising rant or paean From feeble prose to poetry divine, Breathing relief into the words that ran From pen to page, through age, by chalk-drawn plan, Plucking aeolian heart-strings of the mind. And now his volume is forever closed And shelved in the great library above, Where it will wait with all great works composed By man, while I, inspired by all his love Of poetry, breathe life into a prayer That God will read him to me when I’m there.

And, in my Christian faith, I have been blessed (in addition to all of the above, with the possible exception of Dave Shields, whose faith, if any, I never knew) by Dr. Hugh MacPhail, who first taught me, in person, that it is possible to be a thinking man and a Christian; by Mr. Joe Taylor, who was responsible for getting me to take seriously my responsibility in the “Brethren” Assembly in which I’d grown up and start participating; by Dr. David Gooding, who delayed my journey into Orthodoxy by a few years and whose book, According to Luke, is still my primary go-to reference for understanding Luke’s Gospel; and by Fr. Lawrence Farley, whose patient and learned and passionate exposition of the Orthodox Christian faith eventually won me over—both in-person and through the many others at St. Herman’s that he helped to bring in—to the depth and the riches of Orthodox Christianity.

Each of these men (and some of the women who have deeply influenced my life whom I haven’t mentioned, such as my mother, my grandmothers, and my wife) is worthy of far more than the mere mention I provide here, and I hope, at some point, to write more about some of them, but the list is still woefully incomplete, not least because it’s missing all those mentors who have had an inestimable influence on my life but whom I have never met: namely, all those whose writings I have read and loved. The dead have a voice too, whether directly, through writing, or indirectly, through the influence they’ve had on others, and should be included since, as G.K. Chesterton has said, tradition is giving our ancestors a vote.

Which brings me to the genesis of this particular post. Anyone who has read anything of my writing will know that I count C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien amongst my mentors. One whom I have largely overlooked until now because he has mostly been lurking in the background is G.K. Chesterton.

Chesterton is one of those authors whose writings I like and appreciate at least some of and in small quantities—and very much in his quotable quotes (which are many). I was deeply affected by the opening chapters of his brilliant book, Orthodoxy, some aspects of which I still refer to today, despite never actually finishing the book. I love his first Father Brown story, and some of the sequels, but somehow got tired of them, and didn’t end up reading all of them. I’m pretty sure that I read the whole of his The Man Who Was Thursday, but I somehow can’t even remember what it was about at this point. I enjoy his whimsical sense of humour, but at some point, for me, it becomes a bit much of a muchness and I find I simply need to put it down, and usually don’t end up returning to it. I must admit that I have felt a little guilty about this, knowing that he was, if not a mentor to, at least a significant precursor to my heroes C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien—but this morning I discovered that perhaps I needn’t feel quite so guilty after all.

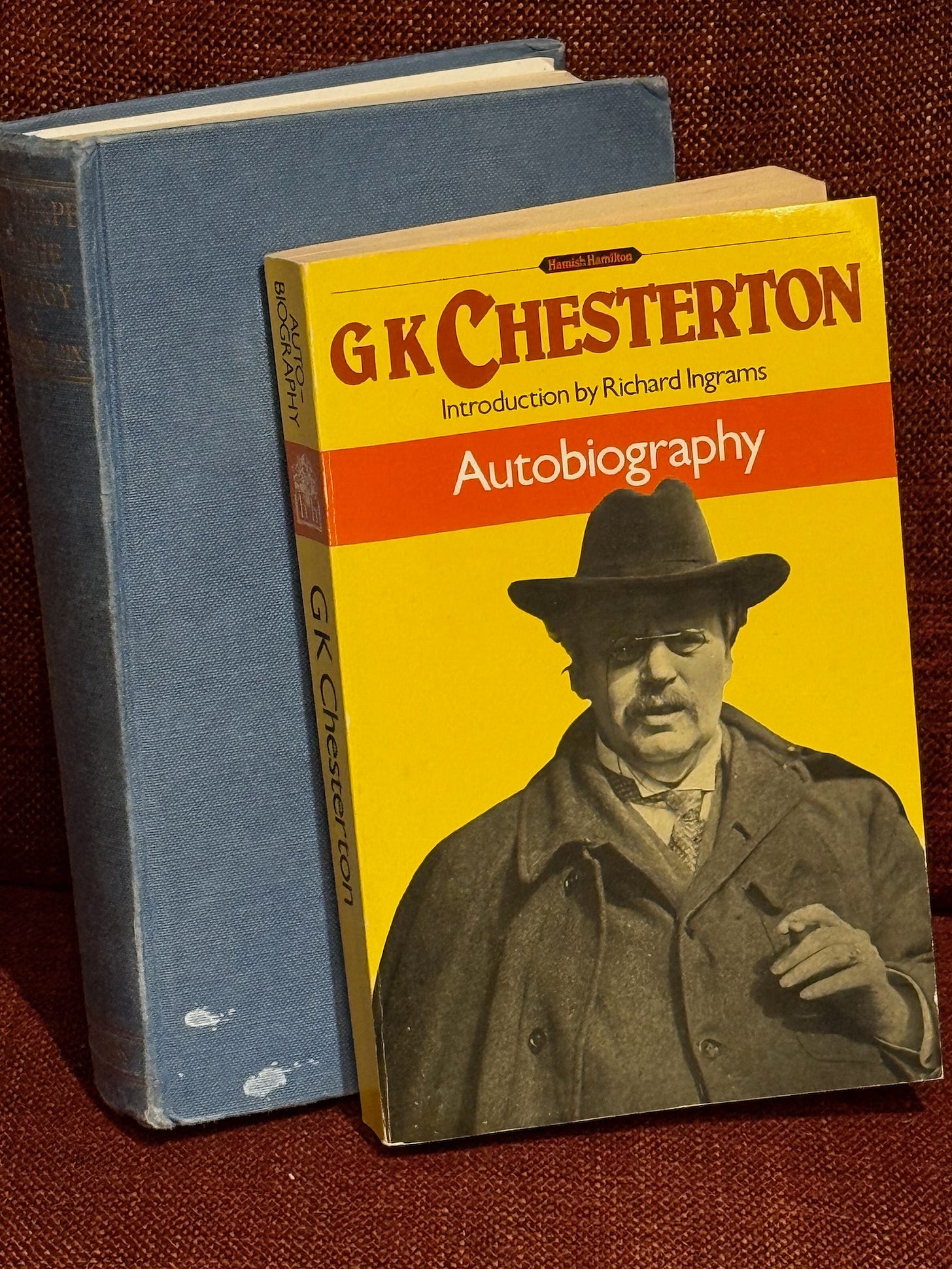

Amongst the many books gifted to me by my mentor, Fr. Lawrence (including a volume on The Shape of the Liturgy, by Gregory Dix, that still graces my bookshelf and that I still haven’t finished some thirty years later!), is G.K. Chesterton’s Autobiography. Fr. Lawrence introduced it to me with a comment very much along the lines of what Ingrams writes in his introduction to it: that it’s actually not much of an autobiography, in the usual sense of the word.

It is scarcely an autobiography in the modern sense at all. There is little that is personal, and nothing at all in the nature of revelation. Chesterton writes less about his childhood than about childhood in general. His account of his schooldays, in addition to portraits of masters and contemporaries contains a number of excellent observations on what it is like to be a schoolboy, but not much about what it was like to be Gilbert Keith Chesterton, aged seventeen. …

It was just that he was absent-minded, witness his famous telegram to his wife—“Am in Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?” He had more important things to think about than mere mundane trifles like dates and engagements. Similarly with this book. It is the work of an absent-minded man who forgets to provide dates and so forth because he feels that there are more significant things in a Life. He could just as well have sent a telegram to his publisher—“Am in Chapter Four. Where ought I to be?”.

And, just before imparting the information that Chesterton’s Autobiography is not really an autobiography in the modern sense at all, Ingram reveals that this—and pretty much all of Chesterton’s most-lauded published work, is not, in fact, his best work. Instead, he says, Chesterton’s best work is really to be found in the innumerable evanescent essays that he published as a journalist.

Throughout his life Chesterton’s medium was the essay—two thousand or more words on a set theme—political, literary, or even religious—a form of journalism which is now extinct but which was then practised by many so-called “Men of Letters”, whose pieces, reprinted in little books, may be found in second-hand bookshops with whimsical titles like Here and There and Odds and Ends. Tossed off to fill a space in a paper, they have deservedly been forgotten. Chesterton tossed them off as quickly as anyone: according to his secretary Dorothy Collins he was capable of dictating one article while simultaneously writing another. But it remains true that these articles are really his best work and that anyone who wants to know what Chesterton was all about should forget the Father Brown Stories and The Napoleon of Notting Hill—both of which can easily come to seem tedious and over-written—and read instead one of those little books of essays with their irresistible List of Contents—“On Christmas”, “On Evolution”, “On Running after One’s Hat” etc. Chesterton got so much into the habit of writing articles that when he sat down to write a book it usually turned out to be a collection of essays on different themes. He himself says here of his book on Browning (page 99): “I will not say that I wrote a book on Browning; but I wrote a book on love, liberty, poetry, my own views on God and religion … and various theories of my own about optimism and pessimism and the hope of the world; a book in which the name of Browning was introduced from time to time, I might say with considerable art, or at any rate with some decent appearance of regularity.”

On reading this, envisioning Chesterton judiciously evaluating with what frequency he should insert the name “Browning” into his book about “Browning” to disguise his own ideas and musings as a scholarly work on the poet, I broke out into a full belly laugh—and came to the conclusion that my only partial appreciation for Chesterton was actually entirely justified.

One does not have to unthinkingly agree with or even appreciate everything that someone says for that person to be a mentor. Indeed, as my father used to say, if two people are in agreement about everything, it only means that one of them is not thinking. And this is true, for me, of all of my mentors, both living and departed. I deeply appreciate them for who they are and all that I have learned from them. But none of them are any more perfect than I am—save one: and even with Him I am not in full agreement, much to my own detriment. But I thank Him, and all my mentors, both living and dead, direct and indirect, for their influence and their guidance towards the Truth, and this, despite my tendency to tire of him when I read too much of him at a sitting, apparently includes G.K. Chesterton. Perhaps the solution here is simply to read no more than two thousand of his words at any one time.

Like you I respect Chesterton, and enjoy his quick mind, but struggle to engage for long periods with him. Maybe its the absentmindedness you mention, Im not sure. But a powerful thinker he surely was!