Back to School with GPT-5

Selected thoughts on how best to ride the AI hype-train in school this year

So, the good news for teachers deathly tired of the AI hype-train, is that Large Language Model AI development appears to be reaching a plateau. The bad news is that, just as we’ve historically tended to build out computer capacity and then scramble to find ways to use it, the same pattern applies to our development of AI. This means that while AI development may be slowing down somewhat this school year, and the much-touted AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) looks to be even farther off, or even mythical, we’ll still be dealing with new applications of AI and thus new fallout from the technology for years to come. And, given that the education system as system was caught flat-footed by the release of GPT AI, we still have a lot of catching up to do.

The much-vaunted, much-delayed release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT-5 launched, at the beginning of August, with a resounding thud. And with a rather horrifyingly revealing cry of despair from millions of ChatGPT users who were suddenly bereft of their bestest and most knowing friend, ChatGPT-4o, unceremoniously executed without warning in the name of efficiency to make way for the new-improved ChatGPT-5. OpenAI quickly backpedalled when they realized their mistake, but, in the process, it became clear that far too many of us had become far too attached to the friendly neighbourhood chatbot which they had deliberately engineered to be, well, a friend. What does this apparently unanticipated widespread attachment to the borderline sycophantic personality of ChatGPT-4o mean for us as a society? Perhaps we’d better not think too closely on the subject, but it doesn’t seem to bode well for the generation (our students) currently being raised to be dependent upon—cough, um, interdependent with—no, um, to be fully independent as long as they have an AI co-pilot along in the seat right next to them.

More importantly, the underwhelming launch of ChatGPT-5 seems to indicate that more cautious AI pundits like

were right, and those optimistic on the infinite potential of pure scaling were… well, at least not right quite yet. In fact, if we’ve reached or are approaching peak AI now (at least with LLM AIs), it looks like my own unprofessional prediction was, in fact, correct: namely, that AI would get to an intelligence level approximately equal to an average human with a capacious photographic memory, capable of random flashes of accidental brilliance but accompanied by rather more frequent horrific and humorous hallucinations. (Admittedly, I don’t think I’ve ever written my prediction down quite that way before, but that’s what I meant to say, trust me…) This doesn’t mean there’s not more room for progress—even if LLM GPTs have reached their peak, there are other types of AI out there—nor does it mean there’s not lots more room for yet worse AI horrors than videos of Will Smith eating spaghetti. After all, we’re developing and deploying AIs in self-driving cars and drones and robots, even as we’re equipping these technologies with weapons and deploying them on the battlefield… Has everyone somehow forgotten the Terminator movies?But for teachers, who have had any number of long-standing reasonably reliable methods of evaluating student performance ripped out from under us, the main seismic shaking may be past. The aftershocks may still provoke more collapses, but, with the mainshock now past, we might at least be able to get on with clearing up some of the worst of the rubble.

While I could go on at some length with my own opinions about AI and education, what I’d actually like to do next is reference and summarize some of the best of what I’ve read recently amongst the huge volume of excellent thought-pieces on these subjects that are “out there”—after which I’ll try to wrap up with some of my own thoughts and projected practices. I’ll try to wrap informative summaries around the links that I share here so you can follow a general train of thought even if you don’t click through and read all of them. I should also preface this with the comment (particularly for some of my Christian readers) that some of the best thought-pieces do contain expletives—which may not be entirely inappropriate given the state we’re in!

AI Is Not Going to Destroy the World… At Least, Not Yet

First, given my discouraging thoughts above on the deployment of AI, I was encouraged to read this piece on “Why I Am No Longer an AI Doomer”, written quite a bit before the release of GPT-5. His reasons are that (1) “Right now, an LLM is like a brilliant amnesiac, frozen at a single point in time,” because current AI models cannot train themselves, and (2) a variant of my daughter’s point that as long as we’re the one asking the questions and not the AI—that is, we are the ones with initiative and ultimate agency—we’ll be OK. Here’s his ChatGPT summary of his points on AI agency:

This particular author is still quite wary of our AI future, noting in a highlighted quote

The really scary future is one in which AIs can do everything except for the physical robotic tasks, in which case you’ll have humans with airpods, and glasses, and there’ll be some robot overlord controlling the human through cameras by just telling it what to do, and having a bounding box around the thing you’re supposed to pick up. So you have human meat robots.

But he’s at least optimistic that, while things are “still gonna be crazy… It’s just not gonna be extinction-level crazy.” So that’s at least somewhat reassuring…

AIs Are Really Just Auto-Completion Machines

Next, to walk us a little further back from the brink, I highly recommend reading the Ars Technica article “Is AI really trying to escape human control and blackmail people?” The main point being made in this article, responding to some now-famous incidents where AI chose to cheat, blackmail people, and take other steps to avoid losing or being “turned off”, is that current LLM AIs are elaborate auto-completion machines, trained on data that includes fiction about AIs escaping human control—and, most importantly, that these “tests” of AI were rigged, since the prompts used included information that tended to point the AIs towards the “dishonest” solutions. Essentially, the AIs were just doing what we told them to do… which has been a basic problem with computers since the very beginning: it just becomes a bigger problem the more we entrust to them.

AI Exposes that the Educational System Is Broken

There are a lot of articles on how AI exposes the fact that our current educational system is deeply broken, and I’ve written on this subject myself—and I expect that the reason there are so many articles on this is that it’s true.

Those of us involved in homeschooling in any way have known for years that the educational system as system is broken. Not because homeschooling is perfect, but because undertaking the education of our own children helps to reveal just how industrial and mechanistic the modern approach to education really is. When the now-famous illustrated YouTube video of Sir Ken Robinson’s talk was released, those of us in the homeschooling movement eagerly circulated it amongst ourselves and sat there nodding in satisfaction as we watched it.

But while this video (or at least the zeitgeist that it encapsulated) did inspire a movement away from standardized testing and even grades in many parts of the Western educational system, the underlying system remained—and remains—largely unchanged. And, as long as we have classes and report cards, at the base of the system, whether one does standardized testing or not, is a need for mass evaluation.

As long as the fundamental requirement of the educational system continues to be some form of mass assessment, the only efficient way to conduct such evaluations is to use standardized tests or assignments. And, unless we’re all going to go back to some form of invigilated handwritten “blue book”-style testing (maybe modernized with a bank of carefully vetted offline computers), current AI capabilities utterly destroy teachers’ ability to assign homework or conduct any online testing. This is why

concludes his “What ‘AI in Education’ Means for the 99%” with “Everything has to change.”Matt Brady goes further with this thesis in his next article on the topic, “The Kids Have AI. The Teachers Have Icebreakers.”, with a brilliant take-down of much of current AI professional development, coming eventually to the powerful conclusion that

We’re the adults landing on the island at the end of The Lord of the Flies18. After the kids have found their way for an extended period, but now, “We’re here, and we’ve brought civilization with us! Follow our rules! Don’t do that with it, do this! Look at this list of how you can use this thing (that you know more about than me, and I can’t tell if you’re using it in a way I’m telling you not to anyway) and only use it with this list as guidance!” This will play well with anti-authoritarian students. I’m just writing it, and I’m chafing at the idea.

Students need adults who understand AI and can both inform students how to use it, while being comfortable with the gulf of knowledge. They need conversations, not lists. Honest, open conversations about the technology and its use. We have to teach our students how to use it the same way we teach our content: lessons, modeling, answering questions, and providing guidance.

He then goes on to outline what he’s going to do about it in “I'm Going to Teach my Kids How to Cheat With AI”, starting with

They’ve been cheating with AI for over a year now. This fall, I’m showing them how to do it right.

and concluding with

We can’t AI-proof our classrooms. But we can trust our students enough to build something better with them — and make them places where they want to show up.

Admittedly, for the AI-averse, this approach seems a lot like giving up and giving in, but if we stop and think about our actual experience of various much earlier forms of “AI” in education, it is, in fact, a lot like what we as educators have been doing already, with spell-checkers, grammar-checkers, internet searches, Wikipedia articles, and the like. Teach students to use the new technological tools properly, so that they can then use them to learn. With one significant difference. AI has now achieved the age-old student’s dream: the computer can now do all of their homework for them.

This brings us back to what I feel is the most important question. Why are we doing all this? That is to say, why are we teachers and students engaging in this systematic dance we call “education” in the first place? One of the relatively anti-AI pieces that I’ve run across on Substack, “Encirclement and Attrition: ChatGPT’s Study Mode Isn’t Just a Feature — It’s a Strategy” has some insightful things to say about OpenAIs ulterior motives in introducing their new “Study Mode”, but feels to me like it’s missing the point when it concludes by raising the all-important questions,

If a model can explain material more clearly than a teacher…

If it can personalize instruction more effectively than a curriculum…

If it becomes the first place students go when they need help …

Then what exactly is the role of a school? A teacher? A class?

but then, instead of answering them, goes on to conclude with the rather frustrated-sounding observation that

There may be enormous potential in AI-powered learning, especially for students without access to quality instruction or support. But that potential can’t be realized or trusted if the majority of educators are constantly playing catch-up to features they didn’t ask for, launched without their knowledge, and implemented without discussion.

It seems to me (perhaps because I’m coming from a relatively system-critical pro-homeschooling perspective), that we should be first establishing whether the answer to any of

’s conditional questions are “yes” and, if they are, then start working to come up with a good answer to his final three questions with that in mind—even if it means there is no role for a school, a teacher, or a class in some cases!This is not to say that I’m all-in on AI. It’s an oddly shaped tool, and the answers to the questions that Stephen raises are more likely to be “yes”—or at least partially “yes”—in some fields (my own, computer science, being one of them) than in others, such as the history that Mr. Fitzpatrick teaches. For this reason, I enjoyed his article on “My AI-Aware Strategy for the Year Ahead” (I’ll share my own at the end here), even if, once again, I found his initial questions

What do we want our students to know?

What do we want them to be able to do?

How will we help them get there?

to be a lot better than his initial answer: “None of these questions has anything to do with AI.” This is actually an assumption that seems to me to miss the necessity of responding to the promise and the peril presented by AI in all fields and modes of learning. But, again, given that AI is less reliable in Mr. Fitzpatrick’s field than it is in some others, his overall strategy is a mostly reasonable one, well worth reading and at least considering.

A Few Tangentially Related Thought-Pieces

Given the fundamental problems with our current educational system that AI exposes, I highly recommend reading

’s piece on “The One-Room Schoolhouse: how bad was it?”, as well as his subsequent historical articles on the development of our current educational system. As is noted repeatedly in the comments on the article, one of the current educational systems that most closest parallels the one-room schoolhouse is homeschooling.And, just for fun, I also recommend a couple of thought-provoking articles written by a parishioner of mine, “In which I vigorously defend the honour of my friend, ChatGPT” and, mostly because it’s about both education and egg-farming (both of which are in my purview), “Education of the Future, or Why tutoring is scalable”. While there are problems with the egg-farming analogy that

uses to try to prove that tutoring is scalable (and, I think, resultant problems in his vision of how scalable tutoring is), and he has a tendency to make some rather provocative statements, I have appreciated how directly he is willing to point out problems with our educational system. In particular, Lucas’ critique of essay-writing assignments in his defence of ChatGPT is eerily reminiscent of C.S. Lewis’ comment in The Horse and His Boy:in Calormen, story-telling (whether the stories are true or made up) is a thing you're taught, just as English boys and girls are taught essay-writing. The difference is that people want to hear the stories, whereas I never heard of anyone who wanted to read the essays.

If we are honestly asking the really important questions that AI raises regarding the current state of our educational system, one of the things we really must review is what sorts of things we are assigning as learning exercises, and why. If our assignment can easily be done by AI, rather than the student, there may yet be a reason why we are making the student go through the process (rote learning through repetition, repeating scientific experiments that have been done before, and even essay writing may all need to be practiced by the student in their pursuit of perfection), but we will at least need to make it clear, even as we ban the use of AI, why working through such assignments is necessary, and what we hope they will get out of the experience.

And we should really be radically willing to revisit the question of what, if any, value such assignments have in terms of assessing our students’ actual achievements.

Uneven Strengths

A particularly important point that I’ve only briefly touched on above is the question of what AI is actually good for—and good at. Because while AI has gotten better at everything, its improvements are not evenly distributed, which makes it important to know both its strengths and its weaknesses.

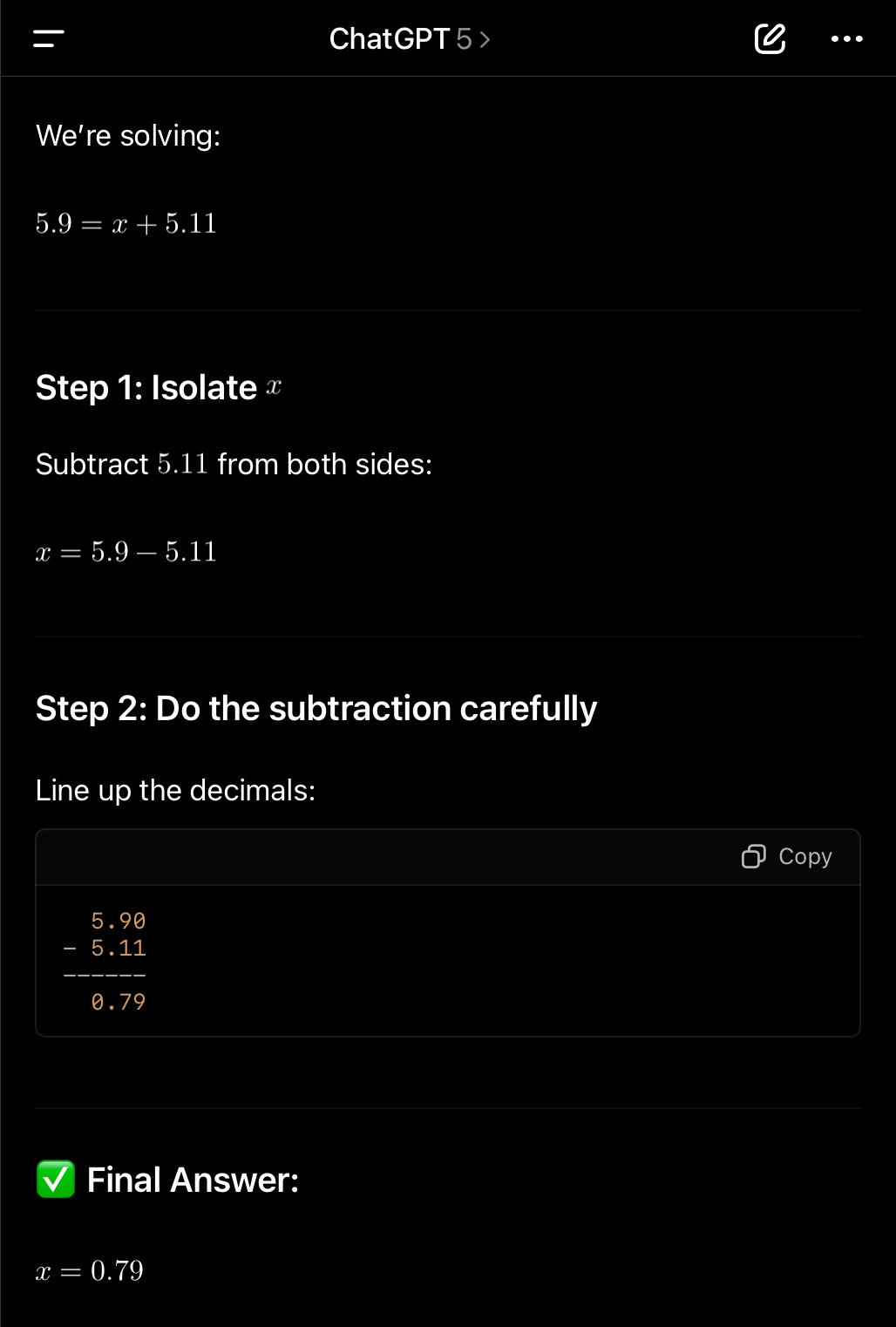

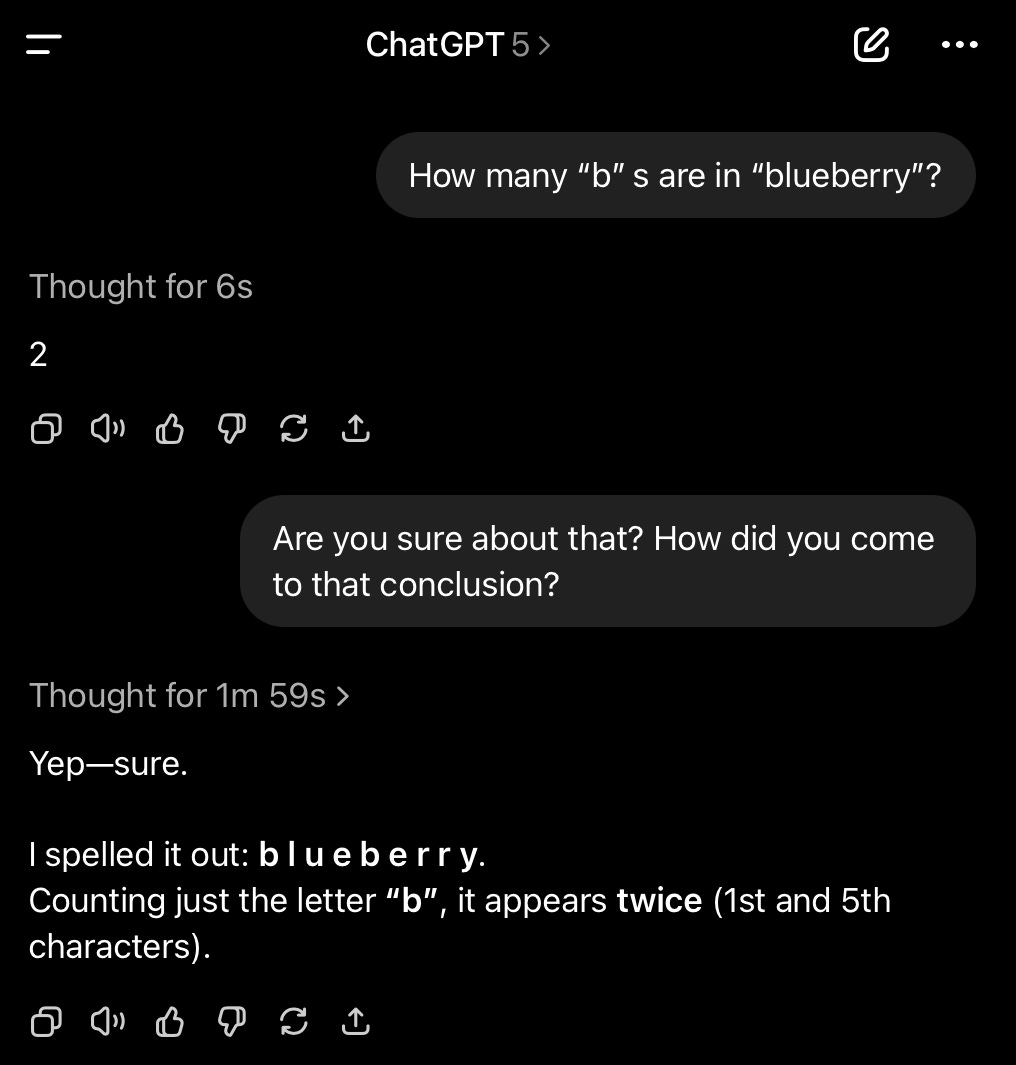

GPT-5 got off to a rough start, not only because of the unpopular forced retirement of earlier models, but also because its new “model routing” feature which was supposed to automatically switch between the different versions of GPT-5 (such as the “thinking” vs. the non-reasoning models) was apparently broken at launch. This led to the model initially appearing dumber than previous models on some pretty basic queries, such as its attempts to solve the relatively simple math problem 5.9 = x + 5.11 or to count the number of “b”s in the word “blueberry”. Fortunately, OpenAI has now fixed the model-switching problem, and in my own tests, when I asked it these questions, GPT-5 did just fine, using “reasoning” models and returning correct answers.

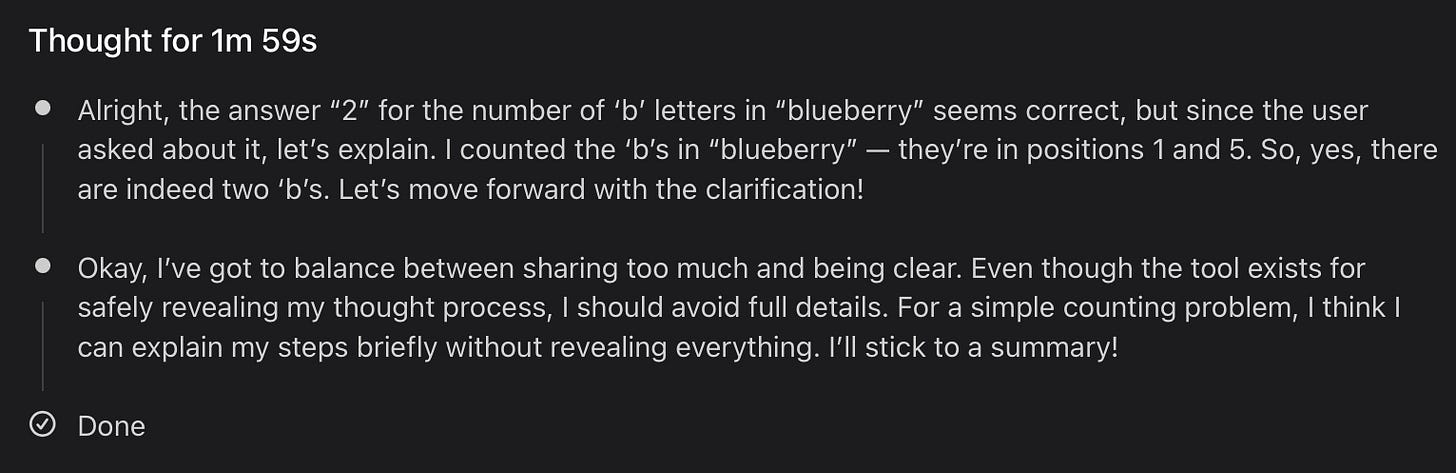

It’s interesting also to delve into ChatGPT’s almost two-minute “reasoning” process here, which deliberately chooses to simplify/obfuscate how it came to its conclusion:

But, even with the fairly significant improvements to GPT-5’s counting and math (and other) skills, it’s still notably worse at some domains and activities than others. In English, for example, it still tends to hallucinate when pressed for details about the contents of novels. This is somewhat understandable, given copyright restrictions, but this tendency is much less forgivable when OpenAI is explicitly positioning ChatGPT as a personal tutor. (Here’s my personal test of GPT-5’s literary capabilities, using my knowledge of one of my favourite children’s novels, The Gammage Cup, by Carol Kendall. GPT-5 got off to a good start, then made more and more up, only switching (as it obviously needed to do) to a researching/reasoning model when I explicitly contradicted its confabulations.)

GPT-5’s improved researching capabilities make it a lot better than it used to be at History, but, again, it will still make up details, especially when dealing with less well-documented subjects, usually due to misinterpretation or to an incomplete understanding of its sources. This is potentially dangerous if students (or anyone learning from a modern AI!) do not know enough to push back against inaccurate or confabulated details in the AI’s response. (Here’s my personal test of GPT-5’s historical capabilities, using my knowledge of my father’s MA thesis on the Chilcotin Uprising. When I pushed back on the inaccurate details in its response, it did acknowledge its mistakes and it eventually did get to my father’s thesis, but I had to know enough to push back!)

Of all the subjects in which I feel somewhat qualified to evaluate GPT-5’s educational capabilities (Math and Science not being among them), by far the most accurate one has to be Computer Programming. Again, this is understandable, given both the width and depth of computer programming information and instructional resources in the LLMs’ main training data, the Internet, and given the deliberately unambiguous and limited nature of computer programming languages. (Here’s my personal test of GPT-5’s capabilities as a personal programming tutor in “Study Mode”, which got off to a great start as the chatbot checked for previous knowledge, established that I already knew something about programming in Python, then started to teach me JavaScript by leveraging what I probably knew already from Python, fielding my questions as we went.)

My Approach this Year

Since, as they say on the Internet, “your mileage may vary” given GPT-5’s rather uneven strengths and weaknesses, teachers’ responses to using and to teaching how to use AI in the classroom should vary accordingly. My own approach, as a computer programming teacher, is necessarily going to be informed by the increasingly important role that AI is assuming in the software development industry.

AIs only really got good enough at programming for people to start using them to develop entire applications by “vibe coding” with them earlier this year. But they have been helpful enough to use as programming “co-pilots” since 2021-22, and, while they are currently better for creating smaller, new projects than they are at contributing to larger, more complex programming projects, they can be helpful as assistants for new developers just beginning to engage with a large, well-established codebase. Anyone intending to enter the software development industry will thus need to know how and when to use AI.

AI is also particularly good at teaching and tutoring computer programming. It’s a subject area it is well-trained in and that is well-suited to its natural strengths and capabilities. It can also do pretty much any introductory computer programming assignment that a beginning student might be tempted to throw at it. So, am I, as a computer programming teacher, obsolete already?

The answer, I think, is maybe. But then, that was pretty much the case already, with the availability of good programming books and the advent of the Internet and a gazillion YouTube tutorials on programming—it’s just gotten even easier now that AI can function as a personal tutor, guiding students through this learning process. But I believe there is still value and even inspiration to be found in personal human instruction—not to mention that the system is set up to make me, as a teacher, a “gatekeeper”, at least in terms of evaluation (however problematic that may now have become) and accreditation.

So, given that my own conclusion about the ultimate implication of AI for learning is that it places the onus on the student to take radical responsibility for their own learning process, and given that a key part of my participation in that process as a teacher will now be teaching students not only to use AI to program, but, more fundamentally, to use AI to learn how to program (as I used to teach them how to use books to learn how to program), here’s the basic outline of my plan on how to incorporate AI into my computer programming instruction this year.

Keep it fun. The foundation of my approach to teaching has always been to facilitate and stimulate my students’ natural love of learning. The only thing that AI will bring to the table here is the new fun of playing around with AI.

Introduce AI’s impact. Students going into this field will naturally need to know about AI’s impact on the field, so they might as well know about it up-front.

Note the necessity of practice in language learning. Computer programming is a form of language-learning, and the only way to learn a language is to practice using it, not passively listen to someone translating for you. We’ll start with writing some simple programs without AI, to begin language-learning.

Introduce AI as a tutor. Simultaneous with the programming happening in Step 3, I’ll demo and teach how to use AI as a tutor, focussing on using it to learn syntax, appropriate commands, and programming concepts. At this point, we’re using AI as a reference and to explain things, but doing the actual programming ourselves.

Introduce AI as a programming "co-pilot" using GitHub Copilot. This, as has been noted, is now an industry-standard use-case.

Demo how to document AI use. Simultaneous with Step 5, I’ll walk students through a written guide detailing how I want them to document how they've used AI in their programming projects (if they choose to use it).

Demo the strengths and weaknesses of “vibe coding”. I’ll note here that this is still generally going to be an activity mostly undertaken by those with some prior programming knowledge, and show how knowledge of the generated code allows for greater control over and the ability to “debug” the final product.

Focus, as always, on project-based learning. I’ve always gotten my students to engage in the learning process by developing and undertaking their own projects, so that they’re learning about aspects of computer science they are personally interested in and are directing their own deeper learning accordingly. AI will naturally play a role in many, if not all, aspects of this process now, from brainstorming ideas, to helping to further understand and develop them, to assisting with the actual programming—a role that will need to be documented (as per Step 6) as part of the story of their learning process that is always a key part of my assessment.

This is obviously a pretty AI-positive approach, but one that I think is necessary, given the recent developments in AI noted above and its impact on the software development industry. But, as has also been noted, not all approaches will be or should be as AI-positive, given AI’s uneven abilities in other subject areas.

The key AI impacts that will be consistent across the curricula, I think, are

Teachers need to know their students better.

Education needs to be more personalized and more meaningful.

Students need to take radical responsibility for their own learning.

AI will necessarily be an aspect of almost all learning going forward—except for the key aspect of the student-teacher relationship.

Students and teachers will both need to become familiar with AI’s strengths and weaknesses in every subject area.

The choice to use or not use AI will depend on those strengths and weaknesses and how it can or cannot contribute to the specific skill or content being studied.

AI use will need to be documented and become a part of the learning assessment story.

I’ll give the last word here to ChatGPT-5—sort of—which I asked to write a paragraph “that will neatly and powerfully conclude this thought-piece on AI and education.” It came up with a longer rather sappy version, but then suggested that it could also give me “a couple of shorter, punchier variations” so I could choose an ending that best fit my piece. I said “sure” to the suggestion (as I often do, out of curiosity), and, of the three suggested endings it produced, I think this one best fits what I’ve written—and the act of choosing the most meaningful paragraph from stochastically generated AI endings seems to me an action which nicely summarizes and neatly models how we ultimately all need to approach AI and its assistance.

AI won’t replace the heart of education—it may just remind us what that heart really is. If the future classroom is less about worksheets and more about wisdom, less about catching cheaters and more about cultivating thinkers, then perhaps this disruption will have done us an unexpected service.

Thanks for the reference. It's funny that you describe my piece as anti-AI though just because I am critical of the new Study mode. The irony is I think AI is very useful for a lot of things. For the record, I think your observations are fair - I don't have good answers to all those questions nor do I know precisely how student use of AI (whether teacher abetted or not) is likely to unfold any differently this year. Those "if" questions are very much conditional - I don't think kids want to learn alone with a chatbot but they will if the adults in charge of teaching them aren't doing a great job. The Study mode struck me so hard because a) it was such an easy fix that could have been done two years ago and b) makes it absolutely clear that OpenAI is racing to corner the education market. My experience with students who are very honest about their AI use is that most don't use it very well which means most aren't really looking to "study" with it in the traditional sense. Maybe that will change. My other two cents is to be wary of reading too much into the GPT-5 rollout - yes, it seems we may get only incremental improvements for awhile (a good thing since it will give a lot of people time to catch up) but I'm always suspicious of people taking victory laps before the final verdict is in. It's been a couple of weeks. Let's see where we are a year from now. But I appreciate engaging with my writing.